In November, we posted these cases and discussion stem to the blog discussion forum and got a number of insightful comments regarding the use of push dose vasopressors in the prehospital environment. This commentary is summarized here.

The term “Push dose pressors” (also known as Bolus-Dose Vasopressors) refers to the intravenous administration of small, discrete doses of vasopressors, such as epinephrine or phenylephrine, to rapidly treat hypotension.[1-2] The routine use of push dose vasopressors (PDPs) originated in the operating room setting to offset hypotension as a side effect of anesthetic medications, such as hypotension induced by spinal anesthesia. [3-4] Subsequently their use gained traction in the emergency department and out-of-hospital setting as a result of popularization by the Free Open Access Medical Education (FOAMed) movement. [1, 5, 6]

While PDP use has become increasingly common, evidence regarding the benefits and/or harms of their use outside of the operating room remains limited. [1] As such we asked our readers the following question regarding their EMS system:

– Are you using push dose vasopressors? If not, why not?

– If so, what are the indications and dosing/frequency?

– What is the protocol for their use and what safeguards against medication error are in place? Are you tracking any quality measures for their use?

Yes… BUT

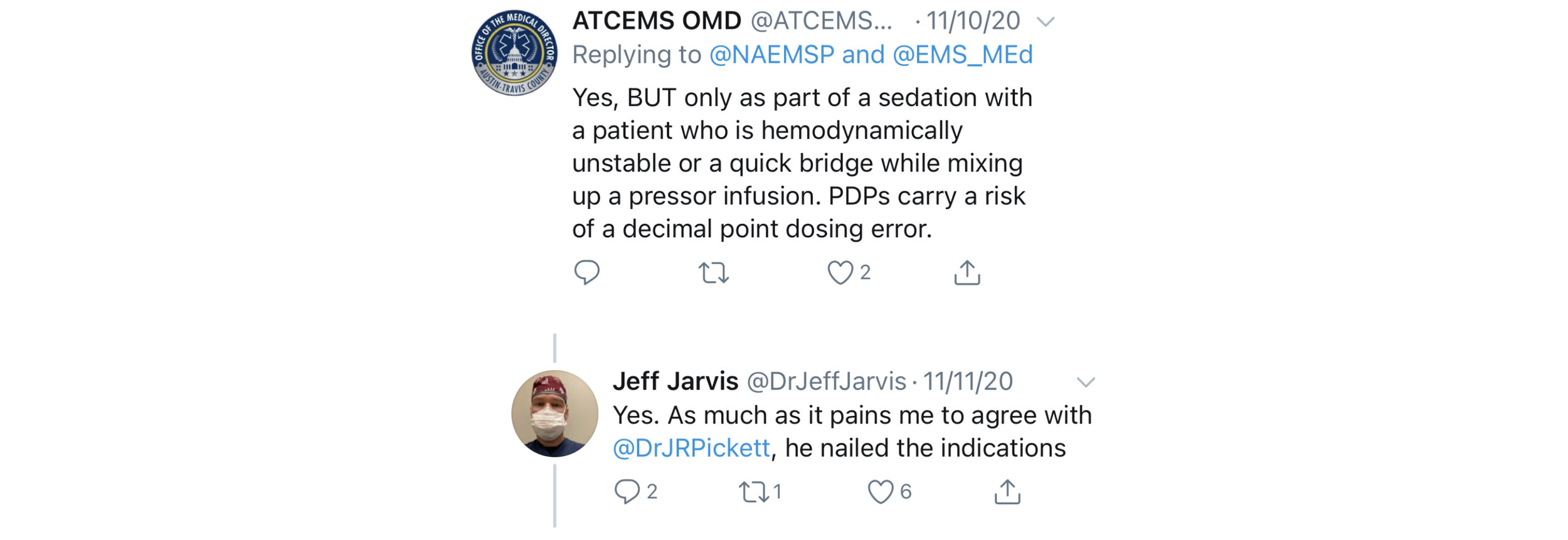

The Austin-Travis County EMS system uses PDPs as a temporizing measuring pending initiation of vasopressor infusion or to prevent peri-intubation cardiac arrest in a hemodynamically unstable patient in need of invasive airway management… an approach shared by Jeff Jarvis of Williamson County EMS.

The reason cited for using only as a bridge? A high risk of medication error. The risk of medication errors in a high stakes, low frequency case is certainly a concern. What does the current literature say regarding risk of medication errors with PDPs?

Rotando et al. (2018) performed a retrospective analysis of PDP use practice patterns, efficacy and safety in critically ill patients ICU patients at a single institution. [7] 146 patients met their inclusion criteria. As expected, PDP use improved blood pressure. However, 17/146 (11.6%) patients had an adverse event associated with push-dose vasopressor use, including dosing errors, administration when patient was not documented to be hypotensive, or administration when patient was already on a continuous infusion vasopressor.

A subsequent retrospective study of Emergency Department PDP use by Cole et al. (2019) also demonstrated a high rate of dosing errors during administration of PDPs. [8] One of the most interesting aspects of this study was that instead of only using standardized chart review, the authors reviewed video of the resuscitations to obtain the majority of their data. They retrospectively identified 249 patients who received PDPs in the ED between 2010-2017 and then reviewed videos of the resuscitation when available (68% of all cases) for dosing errors, hemodynamic consequences of administration and documentation errors. They found that adverse hemodynamic events (defined as HR > 140, new bradycardia (HR < 60), SBP > 180, or development of ventricular tachycardia) occurred in 39% of all cases (27% in the phenylephrine group and 50% of the epinephrine group). Human errors occurred in the care of 19% of patients, including administering a dose different than the intended dose (3%). Dosing errors included anywhere from 10-fold overdoses of phenylephrine or epinephrine to a 100-fold dosing error of phenylephrine. The risk of medication error was significantly increased when an ED pharmacist was not present. Of note, the average time for patients to be started on an epinephrine drip was 8 min, whether or not an ED pharmacist was present, leading the authors to making a conclusion very similar to that of @ATCEMS/Jason Pickett:

“In select patients with shock whose physiology cannot tolerate the several minutes required to prepare a vasopressor infusion, the improvement of blood pressure and vital organ perfusion imparted by push dose pressors may outweigh potential adverse effects. However, push dose pressors could be deleterious to patients whose outcomes are not likely to be improved with this stop-gap therapy (e.g., those with hypotension who will rapidly correct with no intervention or fluid resuscitation, or those with hypotension but not shock). An important area of future research will be determining the patient population most likely to benefit from this therapy.”

What about risk of error in EMS-based studies of PDP use?

Nawrocki et al. (2019) characterized hemodynamic effects and adverse events associated with push dose epinephrine use during critical care aeromedical transport.[9] They retrospectively studied patients who received at least one dose of push dose epinephrine to correct documented hypotension (SBP < 90 mmHg or MAP < 65) following the introduction of a protocol directing administration of 10-20 mcg of push dose epinephrine every 2 minutes until vitals normalize or the vasopressor infusion is ready to start. In this study, they found that of the 100 doses of push dose epinephrine administered over a two year period, 94% were deemed “appropriate” in terms of dosing and indication.

Patrick et al. (2020) evaluated the use of push dose epinephrine in ground-based EMS transport. [10] They performed a one year retrospective chart review of all patient care records where a patient was treated for hypotension (defined as SBP < 90 mmHg) with push dose epinephrine following a protocol very similar to that of Nawrocki et al. They specifically excluded patients whose initial presentation was cardiac arrest. There was one documented medication error amongst 43 cases (2.3%), which was related to a change in the epinephrine stock concentration from 1:10,000 concentration to 1:1,000 concentration secondary to drug shortages.

Of note, in neither of the above EMS studies was the primary objective to evaluate the incidence of medication error.

Is a Bridge Really Necessary?

The most common cited indication for the PDPs is as a bridge to vasopressor initiation. In the Cole et al. study, the average time was 8 min and neither of the prehospital studies were set up to measure this interval. It is thus worth considering whether there is, in general, a different time to initiation a vasopressor initiation in the field versus in the ED.

Some of the commentary addressed this very issue:

The benefit for PDP is iatrogenic hypotension from a procedure (RSI) or you walk in and the patient is peri arrest… Appropriate check lists and references after training can help avoid medication errors if pre made medication syringes aren\’t available. Depending on crew configuration you may not be saving significant time mixing up a stick of pressor vs a bag.

-Shane O\’Donnell

We do not currently utilize push dose pressors in the University of Missouri system. We have a pretty aggressive protocol for initiating pressor infusions, including getting one setup for all post-ROSC patients. I have not seen patients decompensate to cardiac arrest without PDP, and to me a couple minutes of hypotension while getting a pressor infusion set up is reasonable and much safer. We also have a strong push for delaying intubation in unstable patients, and my EMS Clinicians have done a good job of embracing that. – Joshua Stilley

Interestingly, in the prehospital study of PDP use by ground EMS [10], almost one half of the administrations were treated with PDPs pre-delayed sequence intubation, most only required 1-2 doses as they received adjunctive treatments such as fluid administration, and only 48% required continuous vasopressor infusion.

Countin’ Drips

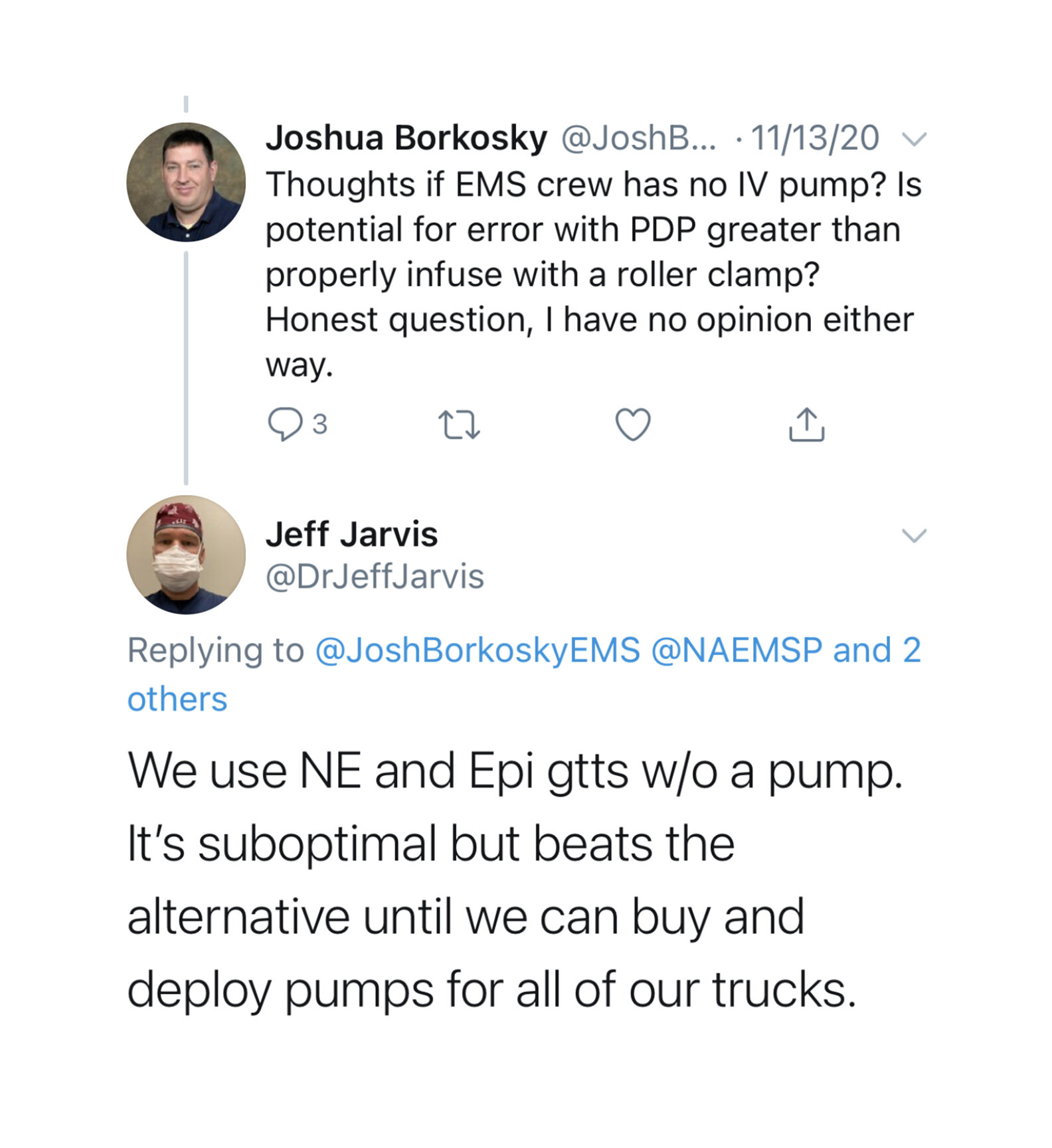

When considering the risk of dosing error in infusions versus PDPs, there remains one key distinction between hospital and most prehospital systems: the availability of IV pumps. This complexity was captured in the following comments by Joshua Borkosky, Jeff Jarvis and Ryan Jacobsen:

We do not use Push-Dose pressors in my EMS System currently. We do use (and I personally use) in the academic ED I practice in however. I\’ve seen no convincing evidence in the literature other than the popular gurus (ex. Weingart) espousing their amazingness. In theory I like it, but several caveats. We use norepinephrine drips currently if pressor needed. We don\’t have pumps however and use a metronome (checklist) to calibrate a rate. It is very imperfect and not awesome. Balancing the risk/benefit of norepinephrine drip without a pump versus mixing a syringe of epinephrine to 10mcg/ml in high risk/low frequency environment is challenging. I have recently found we can get pre-mixed push dose epinephrine (2 month shelf life) so mixing would not be a concern, but likelihood of use versus constantly rotating stock every 2 months in large service has logistics/cost issues. I like the concept in theory. If you have a phenylephrine AND epinephrine premade syringe for push dose you could avoid all need for “drips/pumps” in the 911 urban/suburban environment. I have mixed feelings. – Ryan Jacobsen MD, Medical Director, Johnson County EMS System, Johnson County, KS

Before we jump to suggesting a cheaper “dial-a-drip” or “dial-a-flow” set up, a 2018 study by Loner et al. tested these devices and found them to be inaccurate and associated with both underdosing and overdosing errors. [11]

Given the concern over accuracy of off-pump IV infusions, some EMS systems, particularly urban/suburban transport systems with shorter transport times, opt for PDPs in place of vasopressor infusions given lack of availability of IV pumps. Given the short prehospital transport times, the prehospital PDP may act as a bridge to the in-hospital infusion in these scenarios:

We use PDPs in LA County. We don’t have pumps, and maybe we should, but most of our transports are less than 15 minutes and PDPs are far simpler to do. We use cardiac Epi diluted 10X (10mcg/mL), 1mL Q 3-5 mins. I just can’t reconcile counting drops/min in the 21st century with all of the tech that we bring to the patient these days. – Clayton Kazan

My system is doing both PDPs and IV drip. I personally stick to PDPs though since we do not have IV pumps. We only have dial a flow devices which are inaccurate at best. I personally feel PDPs are safer because you know exactly how much you are giving because you are in control. I mix 1mg Epi in 500ml NS and give 10-20mcg pushes. – Matt King

So, what about that most important quality measure – patient outcome?

So far, all the research we have discussed has evaluated the effect of push dose pressors on hemodynamic parameters, which theoretically serve as surrogate markers for improved outcome because of the known association between hypotension and adverse outcomes, especially for cardiac arrest and traumatic brain injury.

But what if we examined actual patient outcomes?

So far, data is limited to retrospective studies alone.

Guyette et al. (2019) examined the relationship between push dose epinephrine and mortality in patients cared for by aeromedical critical care transport service. They performed a retrospective case-cohort study that included patients > 14 years of age with SBP < 70 mmHg. In 2015, the service introduced a protocol for administration of 100 mcg of IV epinephrine (a dose ~ 5-10 times higher than typical PDP dose) to patients with preserved pulses and SBP < 70 mmHg. This was to be accompanied by volume resuscitation followed by norepinephrine infusion. Each patient who received push dose epinephrine was matched to two historical controls using demographic and prognostic data including age, gender, shock type, weight, index vital signs at first hypotensive episode, and pretreatment characteristics including CPR, defibrillation, transcutaneous pacing, needle thoracostomy, vasopressor administration, intubation or arrhythmia. Interestingly, 30-day survival was lower in patients who received push dose epinephrine (36% vs. 56%) and was significantly different in an adjusted analysis (p=0.01). However, given the retrospective nature of the study, it remains possible that the patients receiving PDPs were still sicker despite attempts to control for likely confounders.

Summary & Take Home

There is variability in prehospital PDP use in EMS practice. While PDPs may have benefit to rapidly address iatrogenic hypotension from a procedure or as a bridge to vasopressor infusion (initiated prehospital or at the hospital destination in the case of short transport times), there are concerns in terms of medication safety and lack of demonstrated benefit in terms of patient outcomes. This remains an area in need of high-quality prehospital research to inform best practice.

Summary post by Maia Dorsett, MD PhD (@maiadorsett)

Edited by Brian Miller, MD (@BrianMillerMD)

References:

[1] Holden, D., Ramich, J., Timm, E., Pauze, D., & Lesar, T. (2018). Safety considerations and guideline-based safe use recommendations for “bolus-dose” vasopressors in the emergency department. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 71(1), 83-92.

[2] Cole, J. B. (2017). Bolus-Dose vasopressors in the emergency department: first, do no harm; second, more evidence is needed. Ann Emerg Med, 1, 3.

[3] Siddik-Sayyid SM, Taha SK, Kanazi GE, et al. (2014). A randomized controlled trial of variable rate phenylephrine infusion with rescue phenylephrine boluses versus rescue boluses alone on physician interventions during spinal anesthesia for elective cesarean delivery. Anesth Analg. 118:611-618.

[ 4] Doherty A, Ohashi Y, Downey K, et al. (2012). Phenylephrine infusion versus bolus regimens during cesarean delivery under spinal anesthesia: a double-blind randomized clinical trial to assess hemodynamic changes. Anesth Analg. 115:1343-13501

[5] Weingart S. https://emcrit.org/emcrit/bolus-dose-pressors/

[6] Weingart, S. (2015). Push-dose pressors for immediate blood pressure control. Clinical and experimental emergency medicine, 2(2), 131.

[7] Rotando, A., Picard, L., Delibert, S., Chase, K., Jones, C. M., & Acquisto, N. M. (2019). Push dose pressors: Experience in critically ill patients outside of the operating room. The American journal of emergency medicine, 37(3), 494-498.

[8] Cole, J. B., Knack, S. K., Karl, E. R., Horton, G. B., Satpathy, R., & Driver, B. E. (2019). Human Errors and Adverse Hemodynamic Events Related to “Push Dose Pressors” in the Emergency Department. Journal of Medical Toxicology, 15(4), 276-286.

[9] Nawrocki, P. S., Poremba, M., & Lawner, B. J. (2019). Push dose epinephrine use in the management of hypotension during critical care transport. Prehospital Emergency Care.

[10] Patrick, C., Ward, B., Anderson, J., Fioretti, J., Keene, K. R., Oubre, C., … & Dickson, R. (2020). Prehospital Efficacy and Adverse Events Associated with Bolus Dose Epinephrine in Hypotensive Patients During Ground-Based EMS Transport. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 35(5), 495-500.

[11] Loner, C., Acquisto, N. M., Lenhardt, H., Sensenbach, B., Purick, J., Jones, C. M., & Cushman, J. T. (2018). Accuracy of intravenous infusion flow regulators in the prehospital environment. Prehospital Emergency Care, 22(5), 645-649.

[12] Guyette, F. X., Martin-Gill, C., Galli, G., McQuaid, N., & Elmer, J. (2019). Bolus dose epinephrine improves blood pressure but is associated with increased mortality in critical care transport. Prehospital Emergency Care, 23(6), 764-771.