By Alison Leung, MD

Setting the Scene

EMS is dispatched to the scene of a motorcycle collision. The patient is unconscious, but breathing and has a rapidly expanding hematoma to the right flank. The patient’s airway is intact, he has equal breath sounds, but his pulses are rapid and thready.

What is your diagnosis? What tools do you have available to resuscitate this patient?

Background

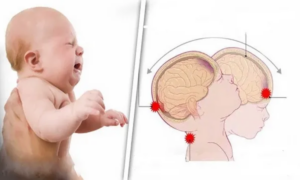

Out of all the causes of shock in patients, prehospital hemorrhagic shock remains one of the more difficult to treat. From a pathophysiology standpoint, the problem starts with the loss of blood volume leading to hypoperfusion and hypotension. In order to compensate for this, the heart increases stroke volume and heart rate to increase cardiac output and the peripheral vascular vasoconstricts. This, however, leads to further hypoperfusion as more oxygen is consumed by the heart and less oxygen can arrive at tissues.

Image from https://persysmedical.com/blog/hypothermia-prevention/trauma-triad-of-death/

To make things worse, this hypoperfusion causes the production of lactic acid, which contributes to trauma induced coagulopathy, which further worsens blood loss and leads to the trauma “triad of death”.

The in-hospital setting benefits from the availability of blood and blood products, however this is not widely available tool for EMS providers to use.

So, what are our options? What is the current evidence for and against prehospital blood administration?

Traditional Treatments

Let’s look first at our standard treatment for all forms of shock: IV fluids and pressors. Do these have any role in the management of hemorrhagic shock?

In theory, IV fluids could help increase blood volume and increase blood pressure, however, this comes at a cost. While IV fluids can help increase volume in general, IV fluids also lack a lot of other things that are being lost – more specifically coagulation factors and red blood cells.

In 2021, Guyette, et al. published a study titled “Prehospital blood product and crystalloid resuscitation in the severely injured patient”, which was a randomized control trial comparing the administration crystalloids, plasma, red blood cells (pRBCs), and plasma+pRBCs in traumatic hemorrhagic shock. The primary outcome was 30-day mortality. Their findings are summarized in the graph and table below:

Figure from Guyette et al. 2021 [1]

Table from Guyette et al. 2021 [1]

To summarize their findings, patients did worse with crystalloids alone and the best with pRBCs+plasma, which intuitively makes sense due to decreased oxygen carrying capacity and worsened coagulopathy that you would expect from IV fluid use. [1]

Shifting gears to pressors – is there any evidence for pressor use in hemorrhagic shock? Let’s think about this logically first. In a patient with acute blood loss, the heart will pump harder (increase cardiac output) and peripherally vasoconstrict in order to increase perfusion pressure. Theoretically, then, pressors would only increase vasoconstriction and lead to worsening tissue ischemia.

In a retrospective ICU based study by Pluard, et al., this is exactly what they found. In this study, they learned that vasopressor use independently increased risk of mortality in patients with hemorrhagic shock. In fact, vasopressor use was seen in 78.5% of non-survivors and in 17.2% of survivors. They also saw increased CPK and creatinine levels in patients that received pressors, which is an indicator of tissue and organ ischemia. [2] Keep in mind, though, that this is a retrospective study and is therefore subject to bias, as patients that received pressors also had higher injury severity scores (ISS), so it’s possible that the patients on pressors did poorly simply because they were sicker.

Unsurprisingly, based on this data, crystalloids and pressors are not the ideal treatment for hemorrhagic shock.

What About Blood Products?

There are two main types of blood products that are available: whole blood and blood components. Whole blood is exactly what it sounds like – red blood cells, plasma, platelets, and coagulation factors given as-is. When donated, blood is separated into components (pRBCs, plasma, and platelets) in order to increase shelf life. Both have been used in the field for hemorrhagic shock. From a logistical standpoint, blood components are theoretically more practical, but what does this mean for patient outcome?

Plasma

In 2018, Sperry, et al. published a trial called “Prehospital Plasma during Air Medical Transport in Trauma Patients at Risk for Hemorrhagic Shock”, also known as the PAMPer trial. This is the original study from which Guyette, et al. drew their conclusions in the aforementioned trial in 2021. Sperry, et al. conducted a cluster-randomized, prospective trial involving 501 patients randomized to either receive plasma or standard care resuscitation. Patients were treated based on which treatment modality the transporting base was assigned.

The following outcomes reached statistical significance:

-

30-day mortality (primary outcome):

-

23% in plasma group

-

33% in standard care group

-

Confidence interval; -18.6 – -1.0; p = 0.03

-

-

Lower 24-hour mortality in the plasma group

-

Plasma group required fewer blood products [3]

A summary of survival is displayed in the graph below.

Figure from Sperry et al 2018 [3]

Component Blood

Component blood is the type of blood products that are typically administered in the emergency room. This is blood that has been separated into three components – pRBCs, platelets, and plasma. Looking back at the previously discussed study by Guyette et al., they had 83 patients total that received RBCs, 147 patients that received plasma, and 38 patients that received pRBCs+plasma. Out of the component groups, they found that pRBCS+plasma improves mortality the most, followed by pRBCs alone, then plasma alone. In this study, all groups reached statistical significance with p < 0.05. [1]

Whole Blood

The administration of whole blood for management of pre-hospital hemorrhagic shock is the oldest method of pre-hospital blood administration and dates as far back as World War II. This practice fell out of favor with the invention of techniques to separate blood components, which are easier to store and can be stored for longer periods of time. However, there is a theoretical benefit to whole blood versus component blood due to its resemblance to the patient’s native blood. It also gives a higher hematocrit and more fibrinogen and allows the simultaneous transfusion of platelets and plasma with red cells, which theoretically corrects trauma induced coagulopathy more efficiently than component blood.

In 2021, Braverman, et al. published a retrospective, single center study using its trauma registry between 2015 and 2019. They analyzed a total of 538 patients who either received transfusion with low titer O+ whole blood (LTOWB) or no transfusion prior to arrival to their trauma center. These patients were further broken down into patients that were intervened upon due to cardiac arrest or prehospital shock.

When propensity matched, they found that the pre-hospital transfusion group had lower ED mortality and lower transfusion volume required. They also found that the transfusion group also had lower 6 hour, 24 hour, and in-hospital mortality, however it’s important to note that they did not reach clinical significance on these outcomes. [4]

Table from Braverman et al 2021 [4]

The Problem

So far all of the literature seems to favor the use of pre-hospital blood products. However, it’s important to note two additional studies.

The first is a meta-analysis published in 2019 by Rijnhout, et al. After a search of all the available studies, they included 9 in their meta-analysis. They concluded that prehospital transfusion of pRBCs alone has no effect on short-term or long-term mortality. Likewise transfusion of pRBCs with plasma had no effect on short-term mortality, but did result in a 49% reduction of odds for long-term mortality. [5]

Most recently, in 2022, Crombie, et al. published a multicenter, randomized control study with a total of 432 patients that were randomized to receive either 0.9% (normal) saline or pRBCs with lyophilised plasma (LyoPlas). Primary outcome was mortality at any point between injury and discharge from hospital or failure to clear lactate or both. Secondary outcomes included death at 3 hours and 30 days of randomization.

Below is the table summarizing their findings.

Figure from Crombie et al 2022

As you can see, they were unable to find any difference between the two groups in their primary outcome. However, death within 3 hours and within 30 days were both lower in the pRBCs and LyoPlas groups, but failed to reach statistical significance.

Conclusions

What does this all mean for prehospital blood products? There is some data for its usefulness in preventing death from hemorrhagic shock. However, most of the available studies are still of low quality and with a relatively small number of patients. It may still be too early to know what is best to do for these patients especially given the cost and scarcity of available blood products.

References:

1. Guyette, F. X., Sperry, J. L., Peitzman, A. B., Billiar, T. R., Daley, B. J., Miller, R. S., … & Brown, J. B. (2021). Prehospital blood product and crystalloid resuscitation in the severely injured patient: a secondary analysis of the prehospital air medical plasma trial. Annals of surgery, 273(2), 358-364.

2. Plurad, D. S., Talving, P., Lam, L., Inaba, K., Green, D., & Demetriades, D. (2011). Early vasopressor use in critical injury is associated with mortality independent from volume status. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, 71(3), 565-572.

3. Sperry, J. L., Guyette, F. X., Brown, J. B., Yazer, M. H., Triulzi, D. J., Early-Young, B. J., … & Zenati, M. S. (2018). Prehospital plasma during air medical transport in trauma patients at risk for hemorrhagic shock. New England Journal of Medicine, 379(4), 315-326.

4. Braverman, M. A., Smith, A., Pokorny, D., Axtman, B., Shahan, C. P., Barry, L., … & Jenkins, D. H. (2021). Prehospital whole blood reduces early mortality in patients with hemorrhagic shock. Transfusion, 61, S15-S21.

5. Rijnhout, T. W., Wever, K. E., Marinus, R. H., Hoogerwerf, N., Geeraedts Jr, L. M., & Tan, E. C. (2019). Is prehospital blood transfusion effective and safe in haemorrhagic trauma patients? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Injury, 50(5), 1017-1027.

6. Crombie, N., Doughty, H. A., Bishop, J. R., Desai, A., Dixon, E. F., Hancox, J. M., … & Perkins, G. D. (2022). Resuscitation with blood products in patients with trauma-related haemorrhagic shock receiving prehospital care (RePHILL): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. The Lancet Haematology, 9(4), e250-e261.

Edited by EMS MEd Editor James Li, MD (@jamesli_17)