by Melody Glenn, MD

Last Wednesday, we met around a picnic table at Rotten City Pizza to discuss Sam Quinones’ Dreamland and the ways in which we as emergency providers can work to combat the worsening opioid epidemic.

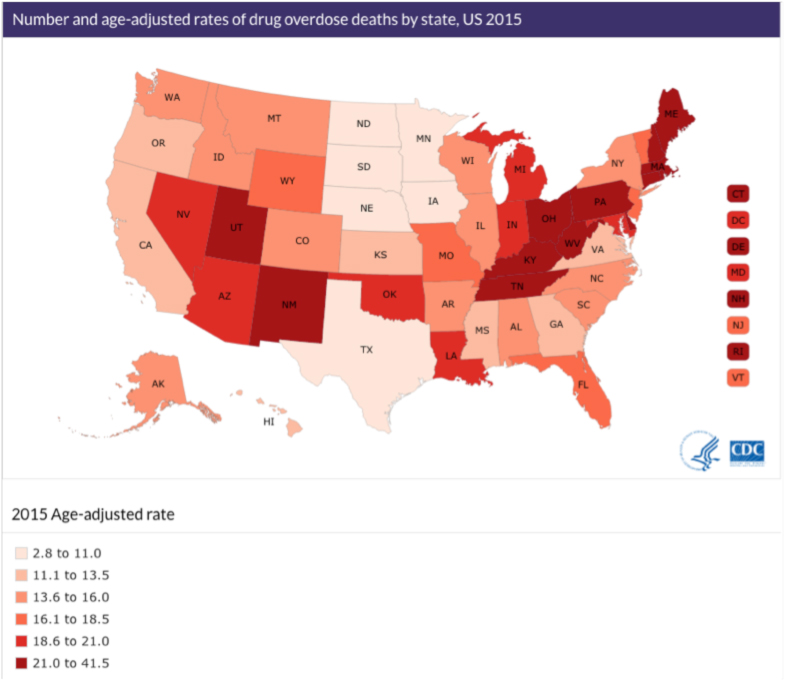

Perhaps no one is more qualified to write such a captivating, multifaceted book on this international crisis than is Sam Quinones, who was a writer in Mexico for over a decade. Dreamland is a story of place, with each chapter rooted in a different city to illustrate how the factors unique to a specific location contributed to the growing problem. Each chapter also revolves around an individual character whose story represents a larger issue. Multiple story lines, initially seeming disparate and unrelated, all come together to form the overall narrative of addiction, and we realize how large and unwieldy the opioid epidemic has ballooned. Quinones shows how a perfect storm of changing business practices in heroin marketing and sales, socioeconomic forces in Xalisco, Mexico and the US rust belt, changing medical beliefs around pain and addiction, and pharmaceutical marketing and development coalesced to form the perfect storm in which opioid overdoses have nearly quadrupled over the last 20 years, now outpacing motor vehicle collisions as the number one cause of accidental death. Quinones focuses on several heavily impacted towns in Ohio, West Virginia, and Kentucky, which helps us make sense of the data regarding alarmingly high opioid abuse/death rates in this region.

In the emergency department, we are protagonists in this dark narrative. We frequently treat patients with opioid dependence, overdose, Hepatitis C, HIV, soft tissue infections, or traumatic injuries sustained while engaged in illicit activities. Unfortunately, we are partially to blame — much of opioid dependence is iatrogenic. A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine earlier this year showed that a single opioid prescription from the ED may lead to long-term use (number needed to harm of 48 pts), and that this risk is greater if the patient is treated by a physician who prescribes relatively more opioids. Of course, we don’t see ourselves a nefarious drug pushes, or even as careless prescribers. Although we are not the highest prescribers, we come fairly close: according to one analysis, emergency medicine physicians prescribe almost 13% of all opioid prescriptions. Even if we aren’t directly getting our patients hooked, we are contributing to a flood of opioid pills onto the illicit market. In some states, there is more than 1 opioid prescription written for every person.

In the prehospital environment, the discussion seems to revolve more around acute overdoses and the use of naloxone to reverse them. Many EMS and police departments are expanding who they train to recognize and reverse an opioid overdose with naloxone — it is no longer just paramedics administering this medication, but also first responders and law enforcement. However, there is increasing worry about the rising cost of treatment as overdoses increase in frequency. In one heavily affected town in Ohio, the local fire department estimates it will spend 50% more than its entire medication budget on naloxone because they respond to so many opioid overdoses; for a town of 48,791, they respond to about 4-5 overdoses a day, and this number continues to increase. Dan Picard, Middletown City Councilman, estimates that each overdose run costs the city $1,104. At this rate, they are not sure how they can continue to afford to provide emergency care to their community.

In addition to whether or not acute reversal is financially solvable, it is also unclear the long-term outcome of such reversal practices on patient outcomes. David Showalter, a sociology PhD candidate at UC Berkeley whose research focuses on opioid overdoses, and Dr. Andrew Herring, a physician double-boarded in emergency medicine and pain management, both believe that unless acute reversals are tied into more sustainable interventions, such as take-home naloxone kits, referrals to syringe exchanges, or referrals to medication-assisted treatment, acute reversals by field providers will have little impact on overall morbidity or mortality.

But that is where things get a little more controversial — what kind of sustainable interventions are we willing to support? Some, including Quinones, argue for jail-based and abstinence-only recovery programs, with the goal of getting everyone 100% clean for the rest of their lives. Unfortunately, it’s rarely so simple. The data shows that fatal drug related overdoses usually increase after people leave jail or “drug-free” rehab. Although it may seem less palatable to some, harm reduction modalities seem to be the most effective in reducing heroin use and fatal overdose.

Harm reduction is based in the philosophy that we must meet patients where they are in order to reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with drug use. Harm reduction spans a large spectrum of practices, including syringe exchange, naloxone distribution to users and their friends/family, fentanyl testing kits (as many of the recent fatal OD’s have involved accidental consumption of fentanyl), medication-assisted treatment (MAT), and supervised injecting sites.

Various emergency departments and EMS systems are starting to distribute naloxone kits to those believed to be at risk of overdose, as well as to their family members and friends. Although some providers worry that providing naloxone encourages further opioid use, studies show the converse is true [1,2,3]. In Massachusetts, opioid overdose death rates are lower in communities with naloxone distribution programs than in similar communities without them[4]. In San Francisco and Chicago, mortality rates among IV drug users decreased after the introduction of naloxone programs [5,6]. Such programs are also considered a cost-effective intervention, in terms of quality-adjusted life years saved per cost spent [7]. So why aren’t more EMS services and ED’s giving prescriptions or naloxone take-home kits? In addition to cost, some may worry about liability if there is an overdose, but many states have enacted good samaritan regulations and third-party prescribing statutes to assuage such fears. Others may worry about providing insufficient training on when and how to use naloxone, but Dwyer et al showed that there are no significant differences in overdose response when training is provided and when it is not [8].

Another successful strategy to reduce heroin use and fatal overdose is through the use of medication-assisted treatment (MAT) with methadone or buprenorphine, which can somewhat be seen as preferred alternatives to illicit opioids. Sometimes, the use of these medications is just a bridge to abstinence, other times, they are taken for the rest of a person’s life. As these programs are so effective, the World Health Organization supports MAT as the first line treatment for opioid dependence for most patients.

Although a cochrane review found little difference between methadone and buprenorphine maintenance in terms of treatment retention and illicit opioid use, in Dreamland, Quinones does not paint the most favorable image of methadone clinics, blaming their dearth of counseling and therapy services on their profit-driven motive (p. 64), and describing them as targets for heroin dealers (p.63-66). Dr. Herring, who runs a pain clinic at Highland Hospital, says his patients describe methadone as more disabling than buprenorphine. When on methadone, they don’t feel clear-headed, and they have to go to a highly-stigmatized place every day to get their dose. Therefore, he believes that buprenorphine, which is just a partial opioid agonist, is the preferred agent. It can be prescribed by primary care providers (with a special waiver) out of their regular clinics, and patients can pick it up at their pharmacy like any other medication. It can also be be administered by emergency physicians, and as such, Dr. Hering has started a buprenorphine induction program out of his emergency department.

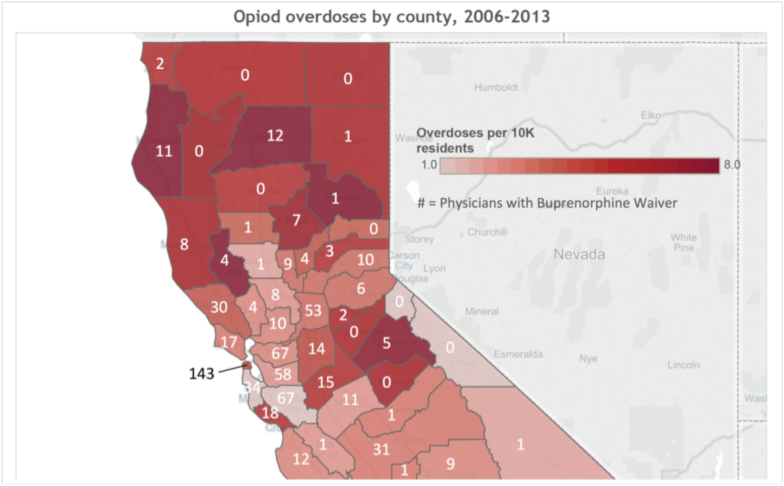

Dr. Kathy Vo, a toxicologist at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital, cautions that we should not be so quick to discount methadone as an effective treatment modality. She believes that the daily clinic visits are vital to the success of some users. Nonetheless, as buprenorphine prescribing is more accessible to emergency physicians, it is bound to become another option in our toolbox for reducing opioid morbidity and mortality. As you do not need a special DEA waiver to provide induction doses for those in acute opioid withdrawal, some emergency physicians are administering buprenorphine in the ED and then referring their patients to other providers who have agreed to continue their patients on maintenance doses. Unfortunately, in many counties heavily hit by the opioid epidemic, there may not be any physicians with a buprenorphine waiver (DEA-x) available to follow these patients.

Source: brighthearthealth.org

That’s where telemedicine comes in: Various start-up’s are offering telemedicine consults to patients in the ED and at home [9]. So via the same tablet that you use for your interpreter, or your stroke neurologist, you can also consult a pain specialist. And your patient can get their outpatient follow-up via their personal phone or computer.

What if your patient isn’t ready to stop using? This may be more common that we would like to think; Dr. Herring says that there is a prevailing mentality amongst providers that patients in the throes of a medical crisis related to opioids — withdrawal, abscess, fall, overdose — are in this perfect window for an intervention, for a “wake-up call.” In his experience, that’s not exactly the case. People in crisis often just want to make it through the crisis, and using opioids may be their more familiar method of coping. But even if they aren’t ready to get clean during that traumatic moment, don’t despair — a different window of opportunity still exists — one for engagement. Give them referral information about where they can access care. When they are ready, they’ll come.

Perhaps this is the most important take-home message for prehospital providers, that we can make a difference simply by providing our opioid-depedent patients with a list of local resources. In the same way that EMS systems have been responsible for creating trauma systems of care, we can start to forge a coheisve network among our emergency departments, harm reduction organizations, and outpatient MAT centers.

Further reading/viewing:

● Information for providers wanting to prescribe and distribute naloxone kits

● ACEP White Paper on ED-Naloxone Distribution

● Physicians who can maintain your patients on buprenorphine

● How to get a Buprenorphine waiver/training (so you can prescribe buprenorphine)

● Narcocorrido about David Tejada, one of the first Xalisco heroin traffickers (p.60-67):

References

1. Seal KH, Thawley R, Gee L, Bamberger J, Kral AH, Ciccarone D, Downing M, Edlin BR: Naloxone distribution and cardiopulmonary resuscitation training for injection drug users to prevent heroin overdose death: a pilot intervention study. J Urban Health 2005, 82(2):303–311.

2. Wagner KD, Valente TW, Casanova M, Partovi SM, Mendenhall BM, Hundley JH, Gonzalez M, Unger JB: Evaluation of an overdose prevention and response training programme for injection drug users in the Skid Row area of Los Angeles, CA. Int J Drug Policy 2010, 21(3):186–193.

3. Strang J, Powis B, Best D, Vingoe L, Griffiths P, Taylor C, et al. Preventing opiate overdose fatalities with take-home naloxone: pre-launch study of possible impact and acceptability. Addiction 1999; 94:199–204.

Walley AY, Xuan Z, Hackman HH, Quinn E, Doe-Simkins M, Sorensen-Alawad A, Ruiz S, Ozonoff A: Opioid overdose rates and implementation of overdose education and nasal naloxone distribution in Massachusetts: interrupted time series analysis. BMJ 2013, 346:f174.

4. Evan JL, Tsui JI, Hahn JA, Davidson PJ, Lum PJ, Page K. Mortality Among Young Injection Drug Users in San Francisco: A 10-Year Follow-up of the UFO Study, American Journal of Epidemiology, Volume 175, Issue 4, 15 February 2012, Pages 302–308

5. Maxwell S1, Bigg D, Stanczykiewicz K, Carlberg-Racich S. Prescribing naloxone to actively injecting heroin users: a program to reduce heroin overdose deaths. J Addict Dis. 2006;25(3):89-96.

6. Coffin PO, Sullivan SD. Cost-effectiveness of distributing naloxone to heroin users for lay overdose reversal. Ann Intern Med. 2013 Jan 1;158(1):1-9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-1-201301010-00003.

7. Dwyer K, Walley AY, Langlois BK, Mitchell PM, Nelson KP, Cromwell J, Bernstein E. Opioid education and nasal naloxone rescue kits in the emergency department. West J Emerg Med. 2015 May;16(3):381-4. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2015.2.24909. Epub 2015 Apr 1.

9. https://www.brighthearthealth.com/ and www.workithealth.com are two examples

From ZSFG’s ED Opioid Withdrawal Treatment Guide

EXCLUSION CRITERIA

Severe liver disease (transaminases 5x normal)

Active alcohol, benzodiazepine, and/or barbiturate use disorder

Psychiatric instability preventing compliance

Chronic pain being treated by pain specialist/on pain protocol

On methadone maintenance therapy

SCREEN PATIENTS FOR AN OPIOID USE DISORDER (RODS SCREENING TOOL)

Patient requests assistance with opioid use disorder

Patient states intent to try abstinence

Endorses IV or prescription opioid abuse

History of opioid overdose

Drug-seeking behavior

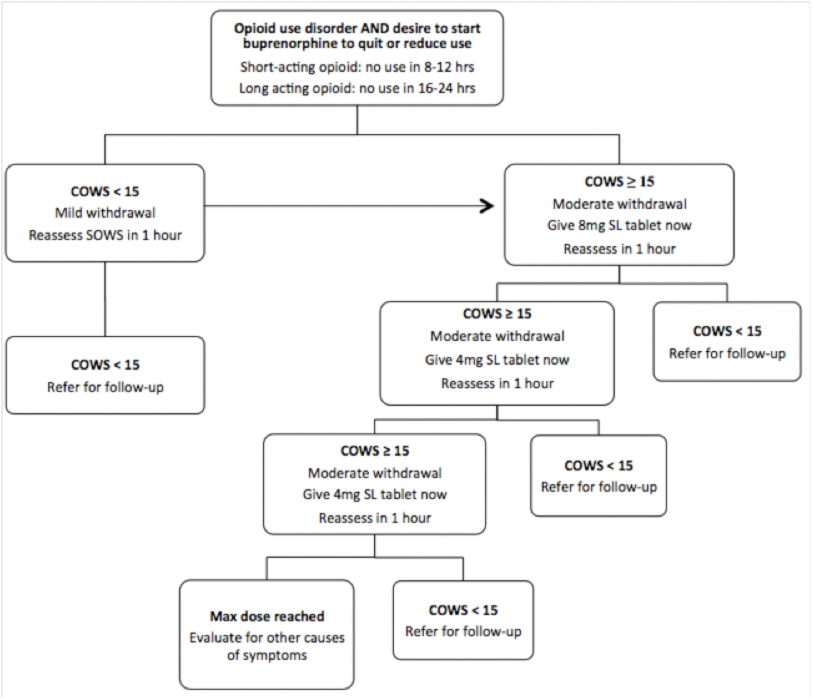

SCREEN PATIENTS FOR OPIOID WITHDRAWAL (COWS)

• Patient has to have been off the opioid for an appropriate time period: 8-12 hours for short-acting opioids, 16-24 hours for long-acting opioids

• Short-acting opioids: heroin, Norco, Percocet, morphine IR, oxycodone

• Long-acting opioids: morphine sulfate ER (MS Contin), oxycodone ER (Oxycontin)

ADJUNCTS TO EASE WITHDRAWAL

• Ibuprofen 400mg PO

• Ondansetron (Zofran) 4mg PO

• Clonidine 0.1mg PO [hold if BP <90/60 or HR <60]

• Loperamide 4mg PO

REFER PATIENT FOR FOLLOW-UP

• If today is SUN-THURS, patient should follow-up in clinic tomorrow.

• If today is FRI & SAT, patient should receive a 1 or 2 day buprenorphine prescription & then follow-up in clinic on the next business day.

Share:

More Posts

Pediatric Cervical Spine Injury and Immobilization

Literature review of pediatric cervical spine injury and immobilization

Article Bites #48: Clinical Care and Restraint of Agitated or Combative Patients

Summary of NAEMSP Position Statement about the care of agitated or combative patients

Article Bites #47: Appropriate Air Medical Utilization

Summary of NAEMSP Position Statement on Air Medical Services Utilization