By Melinda Johnson, EMT-B

One could say that MacGyver is the patron saint of EMS. Prehospital professionals pride themselves on innovative solutions to patient care. Most frequently this takes the form of the work that goes into delivering a packaged patient to the right hospital in a timely manner no matter where, what time of day, and in what situation they originally presented. Less frequently, but no less importantly, this takes the form of innovative solutions to patient care on a system-level. Occasionally, this requires modification of a scope of practice limitation caught under statute or regulation.

Anaphylaxis is a potentially lethal multi-system allergic reaction triggered by an exaggerated immune response. The signs and symptoms of anaphylaxis include bronchospasm, urticaria, pruritis, angioedema, gastrointestinal symptoms (diarrhea, nausea, cramping), cardiac arrythmmias and hypotension [Figure 1]. These symptoms occur on a clinical continuum and can develop over time. Most anaphylaxis occurs in the prehospital environment.

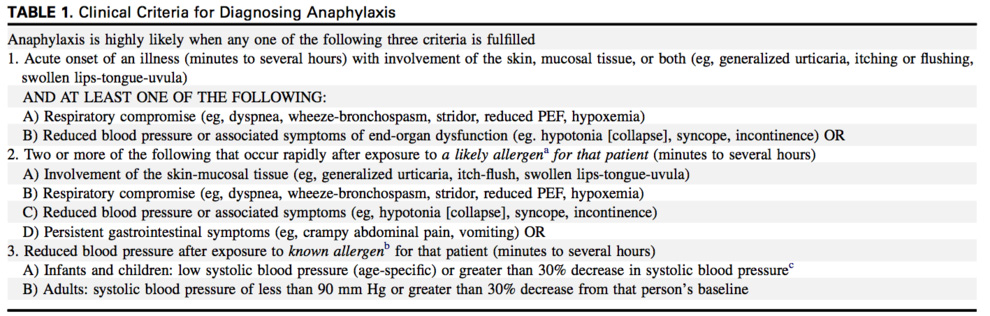

Source: Simons, F. E. R., Ardusso, L. R., Bilò, M. B., El-Gamal, Y. M., Ledford, D. K., Ring, J., … & Thong, B. Y. (2011). World allergy organization guidelines for the assessment and management of anaphylaxis. World Allergy Organization Journal, 4(2), 13.

Many studies have demonstrated that the treatment of choice for anaphylaxis is epinephrine [1]. Death from anaphylaxis occurs either through respiratory compromise or circulatory collapse. The treatment of anaphylaxis is about as time-critical as it gets. In a study of 202 patients who died of anaphylaxis in the UK from 1992 to 2001, onset of symptoms to death took 10-20 minutes for medications, 10-15 minutes for insect stings, and 25-35 minute for food exposures [2]. In two cases series comparing near-fatal and fatal anaphylactic reactions, a > 5 minute delay in epinephrine administration from time of onset of significant symptoms was closely associated with death [3,4]

Ideally, epinephrine is self-administered by patients via auto-injector as soon as severe symptoms occur. However, in many cases, patients either do not have their auto-injector or are having a first allergic reaction and need EMS to provide this potentially life-saving intervention. In the National Scope of Practice model, EMTs are allowed to help patients administer their own medication, but administration of IM epinephrine is left to the AEMT level. Studies published after these guidelines demonstrated that EMTs can administer epinephrine under appropriate circumstances given adequate training [5]. In 2011, NAEMSP published a position statement supporting administration of epinephrine by BLS providers, citing that it “is imperative that EMS providers have the capability to administer epinephrine in a timely fashion.” [6]

While the majority of states allow BLS providers to administer epinephrine, they require that it be administer in the form of an epinephrine auto-injector (EAI). Here in New York, the exponentially increasing cost in epinephrine auto injectors made it difficult for agencies to keep them stocked on their emergency vehicles. Despite the financial challenge posed by EAI, we knew that we couldn’t absolve such a lifesaving drug from our medical supplies. It would be unethical and harmful for our patients. We needed a solution (pun intended).

The Check & Inject NY project was born out of an increasing need for an alternative to the epinephrine auto injector. Several other states had used a lower-cost solution to the epinephrine auto-injector problem: syringe injectable epinephrine. A 2016 survey of all 49 states (excluding Texas because of variability in practice within the state) identified 13 states that allowed BLS providers to draw up epinephrine from an ampule and administer it by syringe [7]. At the time of the survey, 7 other states (including New York) were considering instituting training programs.

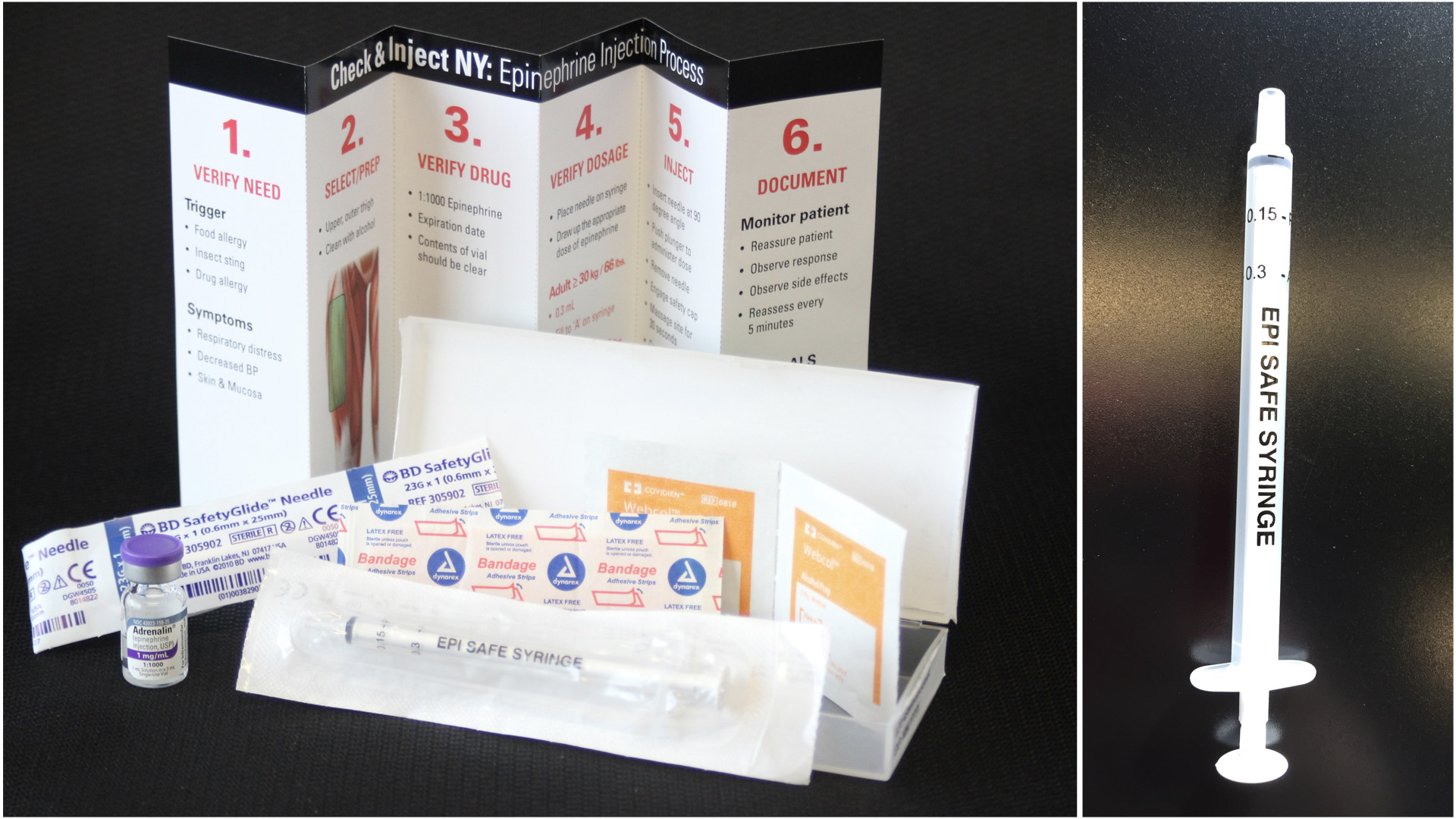

The idea of having basic EMTs draw up epinephrine seemed to be the best solution to the auto injector price hike. After reviewing the syringe-injectable epinephrine project developed by King County Medic One in Seattle Washington, we decided to have a specialized syringe manufactured to prevent dosing issues. We worked with CODAN Medical ApS, a company based in Denmark to develop a syringe with just two gradations on it, one for pediatric patients and the other for adult [Figure 2]. With this simple change, we avoided dosing errors throughout our project.

We quickly realized that given the distribution size of this project, it was unrealistic to put together and distribute all these kits ourselves. We entered a partnership with Bound Tree Medical to keep up with the demand for our kits state-wide. Through this partnership, we also provided a seamless transition to prevent further delay for our agencies to obtain the cost effective Check & Inject kits.

In EMS (and medicine in general), an intervention is only as useful as the training and quality assurance that accompanies it. The Check & Inject NY team created several different tools to be able to make this project successful. We created an entire training program for each agency participating to ensure each provider was refreshed on the use of epinephrine and when to choose adult over pediatric dosing. This training included a skills station in which each provider familiarized themselves with the syringe, the process of drawing up epinephrine, and the process of intramuscular administration. Additionally, students were provided pre and post tests, whose purpose was to evaluate the training and not necessarily the provider’s knowledge of the learning objectives. This was to ensure completeness of the training program so that we were able to provide uniform education not just to local participating agencies, but to agencies statewide.

As quality assurance was a key component to our pilot program, we established a physician phone line that enabled us to have an on-call physician 24/7 for each administration during the pilot program. Once the provider used the syringe epinephrine kit, they were to call this phone line to discuss with the physician about the administration process as well as potential concerns. The physicians then entered the data to a Research Electronic Data Capture database (REDCap) allowing the agency to maintain HIPPA compliance. Additionally, the phone alert itself, triggered a replacement kit to be sent to that agency at no additional cost.

In the active demonstration project phase, 638 agencies participated across the State. There were 83 administrations of check & inject epinephrine. All administrations were deemed indicated by physician consultation and none resulted in injuries for the patients or providers. It was found that kit usage was also utilized for asthma exacerbation. This lead our team to add asthma exacerbation as another Check & Inject kit indication. Interestingly, a provider reported that a patient stated that the syringe epinephrine kit was a less painful than an EAI as a method of receiving the medication.

On May 24, 2017, the project was formally adopted by the New York State Department of Health Bureau of EMS and Trauma (BEMSAT) with the support of the Commissioner of Health through the issuance of Policy 17-06. This was a tremendous achievement and expansion of the BLS scope of practice in New York State. The Check & Inject NY demonstration project is the largest of its kind ever undertaken in the State’s history, requiring collaboration on the part of many individuals. Many other states across the nation have inquired about our project and are looking to start ones of their own.

Patient care starts with basic life support and should not be limited by the outrageous and unnecessary hikes in medication cost. Rising drug costs, shortages, and evidence-based medicine require us to change our practice in order to do what is best for our patients. The importance of training and quality-control cannot be underestimated as we advance practice to ensure that our best-intentions are realized.

References

1. Kemp, S. F., Lockey, R. F., & Simons, F. E. R. (2008). Epinephrine: the drug of choice for anaphylaxis–a statement of the World Allergy Organization. World Allergy Organization Journal, 1(2), S18.

2. Pumphrey, R. (2004). Anaphylaxis: can we tell who is at risk of a fatal reaction?. Current opinion in allergy and clinical immunology, 4(4), 285-290.

3. Sampson, H. A., Mendelson, L., & Rosen, J. P. (1992). Fatal and near-fatal anaphylactic reactions to food in children and adolescents. New England Journal of Medicine, 327(6), 380-384.

4. Yunginger, J. W., Sweeney, K. G., Sturner, W. Q., Giannandrea, L. A., Teigland, J. D., Bray, M., … & Helm, R. M. (1988). Fatal food-induced anaphylaxis. Jama, 260(10), 1450-1452.

5. Rea, T. D., Edwards, C., Murray, J. A., Cloyd, D. J., & Eisenberg, M. S. (2004). Epinephrine use by emergency medical technicians for presumed anaphylaxis. Prehospital Emergency Care, 8(4), 405-410.

6. Jacobsen, R. C., & Millin, M. G. (2011). The use of epinephrine for out-of-hospital treatment of anaphylaxis: resource document for the National Association of EMS Physicians position statement. Prehospital Emergency Care, 15(4), 570-576.

7. Brasted, I. D., & Dailey, M. W. (2017). Basic Life Support Access to Injectable Epinephrine across the United States. Prehospital Emergency Care, 1-6.

EMS MEd Editor: Maia Dorsett, MD PhD (@maiadorsett)