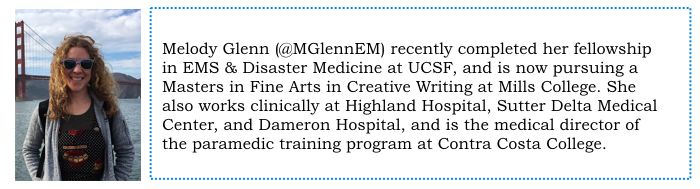

by Melody Glenn, MD

From 2008-2012, Francisco Cantú worked as an agent with the U.S. Border Patrol in the deserts of Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona. The Line Becomes a River is a memoir describing his experience, and like any talented memoirist, he uses his individual story to tell a bigger truth: violence has a way of seeping into the lives of those residing and working in the borderlands, and uniting over our shared humanity must be part of the solution. His mom eloquently describes the way Cantú himself was affected by the work:

You spent nearly four years on the border. You weren’t just observing a reality, you were participating in it. You can’t exist within a system for that long without being implicated, without absorbing its poison. And let me tell you, it isn’t something that’s just going to slowly go away. It’s part of who you’ve become. So what will you do? All you can do is try to find a place to hold it, a way not to lose some purpose for it all (231).

These words could also apply to those working as first responders, medics, and emergency medicine providers. In our daily work, we come face to face with horrors that other people rarely see. We bear witness. Similarly, Cantú describes finding people in the desert in various states of extremis: extremely dehydrated and overheated, victims of brutal violence, and near the brink of death.

Although the personal vignettes he shares about those crossing are heartfelt, they alone are not what make Cantú’s memoir so powerful. It is the bigger themes that link them together into a unified narrative, the references from poetry and sociology that deepen the work, and the beauty of his writing that really make the book shine.

The memoir is split into three parts. In the first, we see the motivation and idealism that lead him to the Border Patrol — he wanted to gain a boots-on-the-ground understanding to go along with the book smarts he gained while studying international relations in college. We are right there with him during his first experiences in the field, learning more about his coworkers and the migrants they apprehend. We see how he is trying to help those in a vulnerable state, even though he is arresting them. He paints his characters as multifaceted, complex individuals, illustrating the grey area of the borderlands.

Cantú shooting and killing a yellow songbird, a metaphor for him crossing a line that cannot be undone, marks the transition to Part II. We see how the daily violence starts to wear on his soul and seep out around the edges. Every morning, he reviews an email briefing about the most recent brutal murders associated with the cartel. Although we often think of the border patrol’s primary mission as stopping immigrants from crossing, they are also trying to prevent the entry of narco-traffickers and their drugs. The victims of the cartel are faceless, nameless:

The summaries included photos of human bodies that had been disassembled, their parts scattered, separated, jumbled together and hidden away or put on display as if in accordance with some grim and ancient ritual. Victims’ faces were frozen in death, reverberating outward from the computer screen without identity or personal history, severed from the bodies they had inhabited and the human relations that had sustained them (86).

It is unknown how many people die due to the war on drugs or crossing the border, but they are often inextricably linked. Reporter Joel Millman wrote that there has been “a shift in the people-smuggling business. A couple of decades ago, workers commonly traveled back and forth across the U.S.- Mexico border… Now, organized gangs own the people-smuggling trade” (93). According to U.S. and Mexican police, this takeover was in part “an unintended consequence of a border crackdown” (93). As Cantú writes, “as border crossing become more difficult, traffickers increased their smuggling fees. In turn, as smuggling became more profitable, it was increasingly consolidated under the regional operations of the drug cartels” (93).

When Mexican president Felipe Calderón took office in 2006, he declared war on the drug cartels. From 2007-2014, the Mexican government said there were more than 164,000 homicides, which does not include the estimated 25,000 missing and disappeared, or those who have died crossing the border into the U.S. while attempting to flee their violence-ridden towns. The Border Patrol recorded over 6,000 deaths between 2000 and 2016. Both Tijuana and Juarez had to increase their morgue operations to keep up with the rising demand. The numbers become overwhelming and have a tendency to turn the individual victims into an anonymous mass. As Cantú puts it:

It is difficult, of course, to conceive of such numbers in any tangible and appropriate way. The number of border deaths, just like the number of drug war homicides… does little to account for all the ways that violence rips and ripples through a society, through the lives and minds of its inhabitants (107).

Even though Cantú was finally in the field, he was no closer to “figuring it out.” He tells his coworker:

When I made the decision to apply for this job, I had the idea that I’d see things in the patrol that would somehow unlock the border for me, you know? I thought I’d come up with all sorts of answers. And then working here, you see so much, you have all these experiences. But I don’t know how to put it into context, I don’t know where I fit in it all. I have more questions now than ever before (142).

Cantú thinks the answers lie in humanizing others, in transforming the numbers and statistics into human stories, and in part III, he does just that. This section focuses on his friend José, who is detained and separated from his family when he tries to cross back into the U.S. after visiting his sick mother in Mexico. He takes the story from the perspective of law enforcement to that of someone victimized by the system, further allowing us to see the border from multiple angles.

Taking a cue from Cantú, I turned to various voices in healthcare to help paint a picture of the unique challenges of practicing medicine in the borderlands. My goal was to highlight their individual perspectives, as personal stories can shed light into dark spaces that numbers alone cannot reach. Furthermore, I believe these stories can form a bridge across divided political views, bringing us to a platform of shared human experience. Stay tuned for interviews with EMS providers, medical practitioners, and patients living and working along La Frontera, from Texas to California.