Yannopoulos D, Bartos J, Raveendran G, et al. Advanced reperfusion strategies for patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and refractory ventricular fibrillation (ARREST): a phase 2, single centre, open-label, randomized controlled trial. Lancet 2020; Nov 13

Background – ECMO and CPR (eCPR)

Refractory ventricular fibrillation (rVF), often called electrical storm, has dismal outcomes which is exceedingly frustrating because we know the cause is likely acute coronary occlusion (~75%). Recent therapies for rVF include double-sequential defibrillation, esmolol, and even ultrasound-guided stellate ganglion nerve blocks. Others have suggested early ECMO in this patient population. The logic behind this approach makes intuitive sense; CPR/ACLS are unlikely to work if you have a 100% left main lesion causing OHCA. One potential solution for this dilemma is to use ECMO as a bridge to cardiac catheterization and revascularization (eCPR). Dr. Demetris Yannopoulos at The University of Minnesota has been an early champion of eCPR with multiple retrospective studies suggesting improved survival when using ECMO for rVF and OHCA. However, the ARREST study is the first randomized trial of standard ACLS vs. eCPR.

Methods

This study occurred from August 2019 through June 2020 at The University of Minnesota and included three transporting EMS systems. Patients were included in the study if they were 18-75yo, presented with shockable rhythm with no ROSC after three shocks, had a body habitus compatible with use of the LUCAS mechanical CPR device, and had a transfer time of < 30 minutes. There were multiple exclusionary criteria, as well, that were all applied in an attempt to select for patients who would have the best opportunity for good functional outcomes AND be most likely to have acute coronary occlusion as the cause of their cardiac arrest:

Exclusion Criteria

· Trauma

· Overdose

· Pregnancy

· Prisoners

· DNR/Nursing home patients

· Terminal cancer

· Opt-out bracelet

· Contrast allergy

· Active bleeding

Patients were randomized on arrival to the emergency department into one of two arms: immediate ECMO with subsequent catheterization/revascularization or standard ACLS in the ED. This is important, as the current standard in many systems is continue to manage the arrest in place.

The eCPR group went directly to the cath lab for immediate cannulation and catheterization. The standard ACLS group got at least 15min of resuscitation or until 60min from arrest. If ROSC was obtained, the standard ACLS group received immediate angiography. If the patient survived to admission, those in both groups got standard cardiac ICU care with targeted temperature management and no neuro prognostication for at least 72hr.

What outcomes were measured?

The primary outcome was survival to hospital discharge with secondary outcomes of safety and functionality (measured by mRS and CPC score) at hospital discharge, three months, and six months.

Results:

Were the two groups similar?

Although many historical specifics were unknown (not surprising for a study of OHCA), the two groups were similar at baseline although there were more women and ESRD patients in the standard ACLS arm. All patients presented with an initial rhythm of rVF. Rates of witnessed arrest and bystander CPR, time to EMS arrival, and prehospital ACLS treatments were similar. No patients had ROSC on arrival to the ED. These patients were SICK with hospital arrival lactates of 10-11, pH values of 6.9-7, and measured ETCO2 levels of 28-33. Six patients were excluded: two with initial PEA, one with a transport time >30min, and three with ROSC after the 2nd shock.

What were the key results?

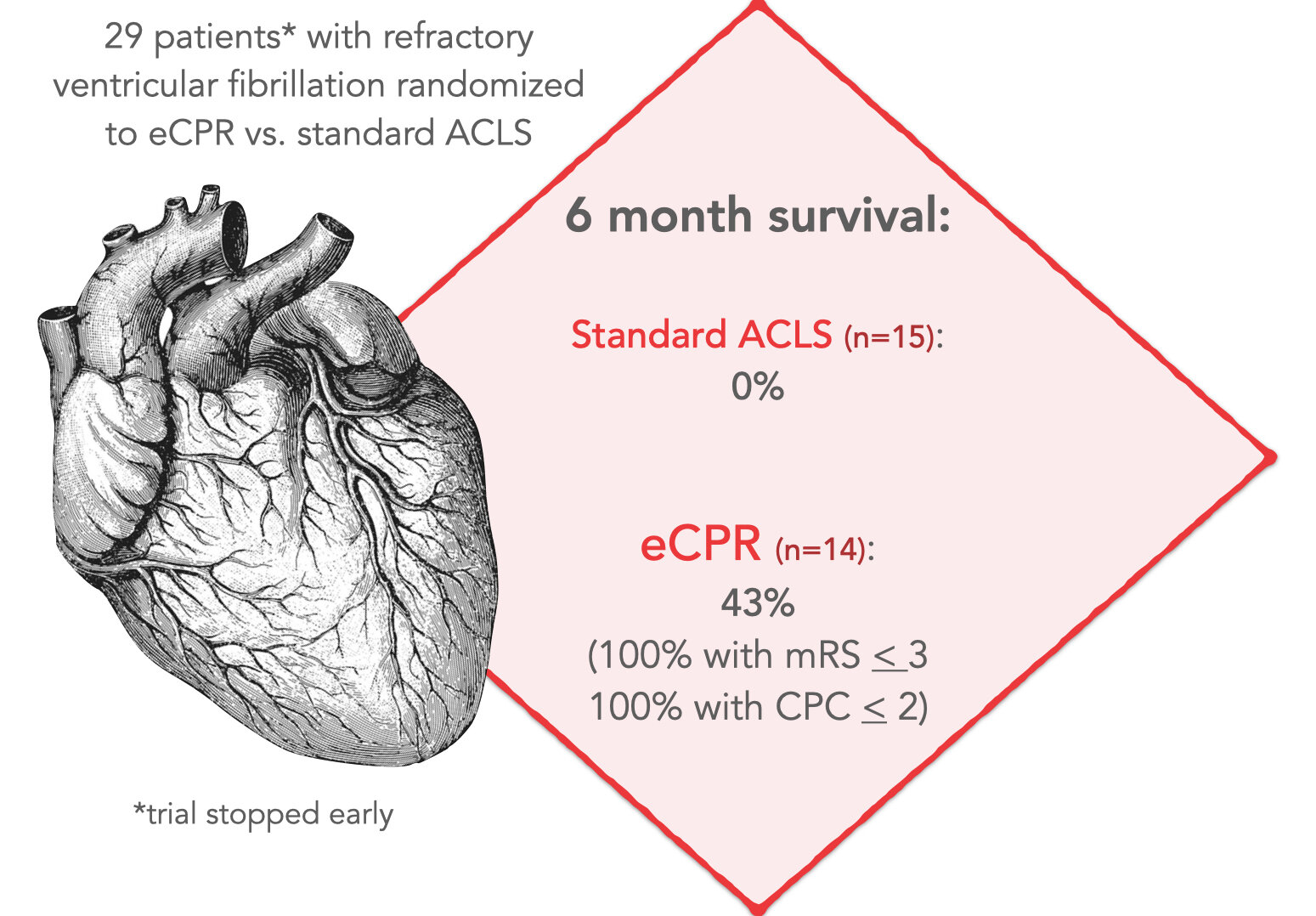

Survival to discharge in the eCPR group was 43% (6/14) vs. 7% (1/15) in those treated with standard ACLS.

But what was the functional status of the survivors? At the 6-month mark, all 6 ECMO survivors had an mRS of 3 or lower. Only 2 of the 15 standard ACLS patients even made it to the cardiac catheterization lab. One died in hospital from cerebral edema and the other after hospital discharge from anoxic injury. Two patients in the eCPR/ECMO group were declared dead prior to cannulation (2 or more of ETCO2<10/PaO2<50/lactate>18 = dead). Six ECMO patients died before hospital discharge due to anoxia/cerebral edema. ECMO complications included one tubing break, two access site bleeds, and one retroperitoneal bleed.

One criticism of this study will obviously be the small patient numbers, but the data safety monitoring board actually stopped the study early due to lack of equipoise.

What would a program like this require?

From a prehospital standpoint, our portion of care will be the beginning in a long process that will require coordination of care across EMS/ED/cath lab/ICU and even rehabilitation. That said, the authors specifically stated that the time from 911 call to ECMO cannulation is the prime predictor of survival. Implementation of an eCPR program will not be something that EMS can tackle alone. A streamlined system of care with a dedicated resuscitation center will be critical and must include ECMO availability with ED, cardiology, an intensive care buy-in. Yes, an eCPR approach is expensive and labor-intensive, but improving survival to almost 50% with good functional outcomes in a condition with an otherwise bleak prognosis seems promising at the very least.

Article Summary by Casey Patrick, MD

Figure by Maia Dorsett, MD PhD