by Nick Wleklinski, MD and Hashim Zaidi, MD

Introduction:

An EMS crew is called to residence of a 39-year old, otherwise healthy male with diarrhea. The patient reports 2 days of diffuse abdominal pain and diarrhea. On evaluation, the patient’s abdomen is non-tender, but he is surprisingly tachycardic, mildly tachypneic, and saturating at 88% on room air with clear lungs on exam. Under normal circumstances, a primary viral respiratory illness would not be the highest on the differential, but in the setting of a pandemic, this is not the case. Precautions need to be taken to ensure safety of the patient and of the crew.

SARS-CoV-2 (named for “severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2”), commonly referred to as COVID-19 or “The Coronavirus”, is an RNA virus in the same family as the viruses responsible for the SARS and MERS epidemics in 2003 and 2012, respectively. This virus causes a viral pneumonia, which can lead to respiratory failure and poor oxygenation. As the illness progresses, some patients experience a hyperinflammatory response, leading to further clinical deterioration. [1] Those who are older and with multiple co-morbidities are at highest risk for deterioration, but young, healthy, patients have also shown a need for critical care support.

COVID-19 has become a strain for healthcare systems around the world, highlighting the lack of personal protective equipment (PPE) necessary to prevent transmission. Social distancing measures put in place by many communities have helped slow transmission or “flatten the curve”, but many people will still become ill with COVID, making it imperative that we continue to take precautions and prepare. Healthcare professionals are a limited resource and are unable to contribute to patient care if sick or on home quarantine, so protecting EMS personnel is key! EMS providers, administrators, and medical directors need to be vigilant about how to identify potential COVID patients, to know how to properly protect EMS crew members while conserving precious PPE supplies, and to be ready to safely transport these patients.

Clinical Considerations:

Symptomatic patients will most commonly have fever and a dry cough, but this is not always the case. Providers should consider COVID infection in anyone with: [2-6]

-

Fever

-

Chills

-

Any respiratory symptoms

-

Hypoxia (even if the patient does not have dyspnea!)

-

Sore throat

-

Muscle aches/myalgias

-

GI symptoms (abdominal pain, diarrhea), which can precede respiratory complaints

-

New loss of taste/smell

-

Recent exposure to anyone with the above symptoms

Those who are more at risk for contracting COVID include healthcare workers, nursing home or long-term residential facility residents, those who are unable to socially distance or isolate, and those who continue to travel.

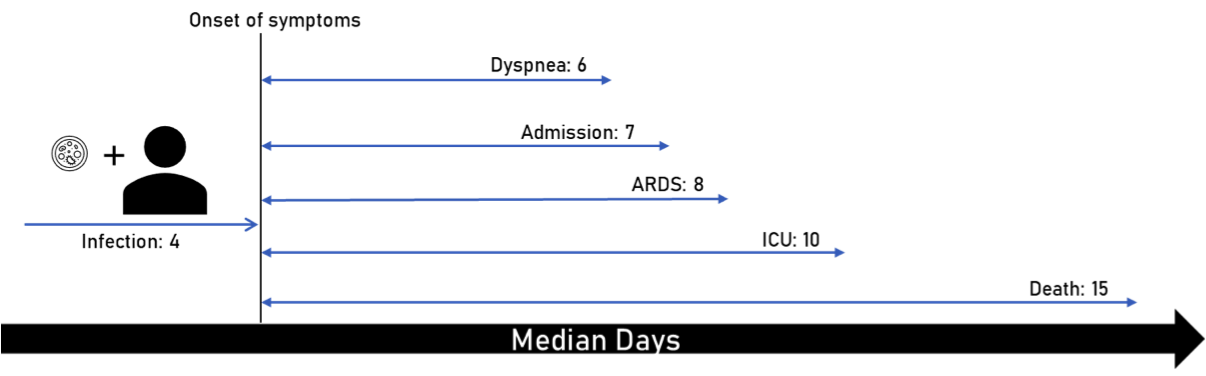

The progression of the illness varies, but there is a tendency for patients to deteriorate very quickly after an otherwise stable course. Therefore, it may be helpful to keep a general timeline (Figure 1) for those at higher risk for severe illness. [7-9]

Patients at a higher risk for severe illness include people 65 years or older, people who live in a nursing home or long-term care facility, and people of all ages with underlying medical conditions, particularly if not well controlled, including chronic lung disease, serious cardiac conditions, immunocompromised states, severe obesity, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, or liver disease. [10]

Figure 1: Median days of symptom onset following infection. ICU bed availability was limited in these studies, resulting in patients developing ARDS prior to transfer to ICU.

PPE Considerations:

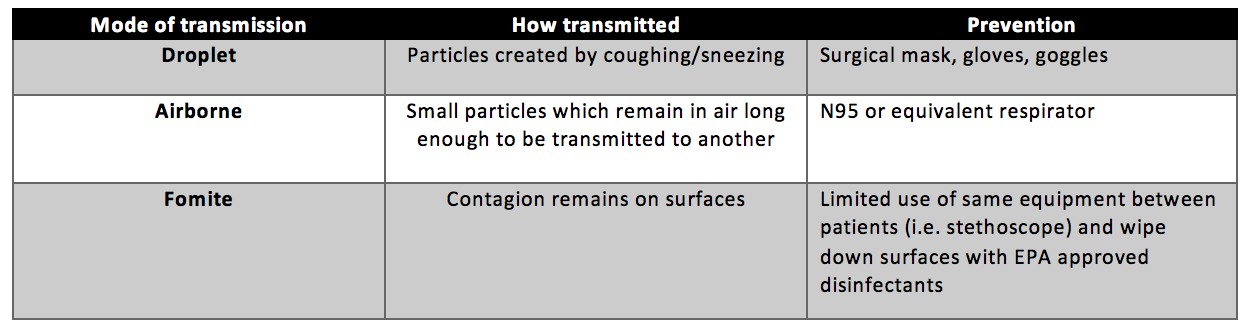

Transmission: Table 1 outlines the various modes of transmission of the COVID-19 virus. The main means of transmission is attributed to droplets created by coughing/sneezing, but there is data that suggests the virus survives in an aerosolized form for a prolonged period. The virus can survive on surfaces. It survives for the longest time on stainless steel and plastic and for the shortest time on cardboard and copper. [11]

Table 1: Transmission modes of COVID19 and how to prevent said transmission

When compared to past epidemics, COVID-19 is proving to be more infectious. R0 (reproductive number) refers to number of secondary cases that result from one person. The higher the number, the more people one person can infect. The R0 for COVID-19 is estimated to be 4.7-6.6 compared to H1N1 and SARS, which have an R0 of 1.2-1.6 and 2.2-3.6, respectively. However, with social distancing and stay at home orders, that number drops to 2.3-3.0. [12, 13] This illustrates the importance of limiting contact to prevent further transmission of the virus.

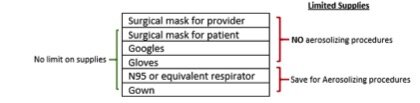

Preventing Transmission: Curbing the transmission of COVID-19 starts by preventing unnecessary exposure. Therefore, keeping a 6-foot distance from the patient, when able, is important. Most of the assessment can be done from this distance and frank respiratory distress can be observed. Limit the number of providers who have direct contact with the patient. Have the patient put on a mask him or herself or provide one on arrival. Since there is evidence the virus spreads via asymptomatic carriers, masks should be worn on all patient encounters regardless of symptoms. [14-16] Furthermore, universal masking policies have shown to be effective at preventing transmission in Hong Kong during this pandemic. [17] If the patient is able, have them walk to the ambulance themselves so that providers do not have to enter the residence. While N95 masks are the most effective protection against aerosolized viral particles, there has been a nationwide shortage of masks. For this reason, surgical masks are a reasonable alternative to N95 masks provided that no aerosolizing procedures are being performed (Table 2). For patients that present in extremis, don full PPE early to allow for uninterrupted and safe care. [18]

Table 2: PPE to use when treating suspected or confirmed COVID patients based on supply availability

Reusing PPE: The lifespan of N95 masks or respirators can be extended by wearing the same mask throughout a shift (extended use) or by donning and doffing the same mask during the shift (reuse) [19]. A surgical mask may also be used over the N95 to protect it from foreign material.

If electing to reuse a mask, hand hygiene is crucial when adjusting or removing the respirator. Touching a contaminated mask can facilitate transmission of the virus via contaminated hands.

Extended use: Keeping the same mask on throughout the entire day or shift (maximum of 8-12 hours)

-

Discard after :

-

Contamination

-

Aerosolizing procedures

-

Contact with patients requiring contact precautions (e.g. C. diff)

-

Reuse: Taking the mask on and off. This is riskier as it requires touching the mask more frequently, which increases risk of self-contamination.

-

Discard after contamination as with extended use

-

Keep in breathable (i.e. paper) bag when not in use

-

DO NOT touch the inside of the respirator; discard if this occurs

-

Use gloves when donning the mask and performing a seal check, take them off after, and put on a fresh set

-

Limit to approximately 5 uses or check manufacturer recommendations

Management of Respiratory distress:

Oxygenation tends to be the principal issue before patients deteriorate. However, many interventions that improve oxygenation increases risk of transmission as they also aerosolize viral particles. Aerosolizing procedures include:

-

CPAP/BiPAP

-

Suctioning

-

Nebulized medications

-

BVM

-

Intubation (ETT or supraglottic)

How to treat:

-

Keep patients upright if possible; this decreases the amount of de-recruitment and improves oxygenation

-

Keep the patient’s SpO2 >90%

-

If using a nasal cannula, place a mask over the nasal cannula

-

Use metered dose inhalers (MDIs) instead of nebulizers

-

Consider using the patient’s medication to conserve supply

-

-

Use epinephrine for severe respiratory distress

-

Adult: 0.3 mg of 1:1000 IM

-

Peds: 0.01 mg/kg 1:1000 IM

-

-

Use a supraglottic airway if more definitive airway management is required:

-

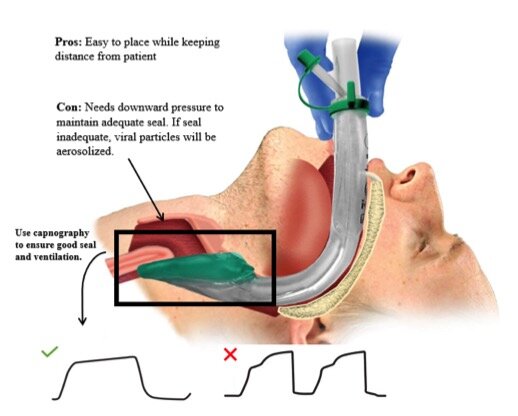

Precautions: Stop compressions while placing a supraglottic airway and consider placing the device before entering the ambulance to decrease potential spread to providers. A proper seal is required to limit unintended aerosolization of viral particles (see figure 2). [20, 21]

-

Consider placing a plastic sheet over the patient

-

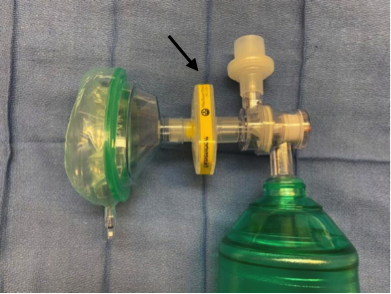

Use a HEPA filter with BVM (figure 3)

-

Figure 2: Use of supraglottic airway for COVID patients. Capnography waveforms indicates proper placement with good seal (checkmark) as opposed to a waveform indicating improper placement (X).

Figure 3. Always use HEPA filters when using a BVM

Who to transport: Some services have adopted protocols to limit unnecessary transport to the emergency room. Figure 4 is an example of a protocol from Alabama used to identify who truly requires transport to prevent overcrowding of hospitals. Details are available on NAEMSP’s COVID-19 resource page. The figure also highlights important differential diagnosis to consider when approaching these patients as well as PPE considerations to keep in mind.

![Figure 4: Sample protocol for non-transport of patients [22]](/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Untitled4.jpg)

Figure 4: Sample protocol for non-transport of patients [22]

Transportation to care facility:

-

Keep the door or window between driver and patient compartment closed

-

If unable to do so, the driver should also be wearing the appropriate PPE

-

-

Turn on ventilation (non-circulating mode) with rear exhaust at max.

-

Notify the receiving hospital so they can prepare and minimize exposure to others

-

Leave rear doors open while transporting patient into hospital

-

Cleaning:

-

If no aerosolizing procedure performed: clean all surfaces that the patient had contact with

-

If aerosolizing procedure performed: clean all surfaces regardless of patient contact

-

Summary:

COVID-19 is a tremendous stressor on the healthcare system, requiring rapid development of protocols that need to remain flexible as PPE supply becomes limited and new information regarding this illness emerges. EMS providers are some of the first providers to come in contact with these patients and the risk of transmission is high. PPE is crucial to prevent spread, but judicious use is imperative in order to prevent unnecessary depletion of an already limited supply. Respiratory support should be provided using only nasal cannula, making sure to avoid aerosolizing procedures such as CPAP, BIPAP, and intubation. Consider preferentially using supraglottic devices if prehospital advanced airway management is required. Encourage non-transport of low-risk patients if your local protocols permit to prevent unnecessary exposure and always notify receiving hospital that a potential COVID-19 positive patient is in route.

References:

-

Gattinoni, L., et al., COVID-19 pneumonia: different respiratory treatment for different phenotypes? . Intensive Care Medicine, 2020.

-

Guan, W.J., et al., Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med, 2020.

-

Del Rio, C. and P.N. Malani, COVID-19-New Insights on a Rapidly Changing Epidemic. Jama, 2020.

-

Xie, J., et al., Critical care crisis and some recommendations during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Intensive Care Med, 2020.

-

Symptoms of Coronavirus. 2020 3/20/2020 [cited 2020 April 30]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/symptoms.html.

-

Wang, D., et al., Clinical Characteristics of 138 Hospitalized Patients With 2019 Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Jama, 2020.

-

Arnold, F., Louisville Lectures: Internal Medicine Lecture series, in COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) Epidemic with Dr. Forest Arnold, D.F. Arnold, Editor. 2020: YouTube.

-

Huang, C., et al., Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet, 2020. 395(10223): p. 497-506.

-

Thomas-Ruddel, D., et al., Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): update for anesthesiologists and intensivists March 2020. Anaesthesist, 2020.

-

People Who Are at Higher Risk for Severe Illness. 2020 4/15/2020 [cited 2020 May 1st]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-at-higher-risk.html.

-

Van Doremalen, N., et al., Aerosol and Surface Stability of SARS-CoV-2 as Compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J Med, 2020.

-

Sanche, S., et al., The Novel Coronavirus, 2019-nCoV, is Highly Contagious and More Infectious Than Initially Estimated. medRxiv, 2020: p. 2020.02.07.20021154.

-

Fraser, C., et al., Pandemic potential of a strain of influenza A (H1N1): early findings. Science, 2009. 324(5934): p. 1557-61.

-

Kimball, A., et al., Asymptomatic and Presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infections in Residents of a Long-Term Care Skilled Nursing Facility – King County, Washington, March 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 2020. 69(13): p. 377-381.

-

Hoehl, S., et al., Evidence of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Returning Travelers from Wuhan, China. N Engl J Med, 2020. 382(13): p. 1278-1280.

-

Moriarty, L.F., et al., Public Health Responses to COVID-19 Outbreaks on Cruise Ships – Worldwide, February-March 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 2020. 69(12): p. 347-352.

-

Cheng, V.C.C., et al., The role of community-wide wearing of face mask for control of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic due to SARS-CoV-2. J Infect, 2020.

-

Prevention, C.f.D.C.a. Interim Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Patients with Suspected or Confirmed Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Healthcare Settings. 2020 4/13/2020 [cited 2020 4/13]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/infection-control-recommendations.html.

-

PANDEMIC PLANNING. 2020 3/37/20 [cited 2020 April 13th]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/hcwcontrols/recommendedguidanceextuse.html.

-

I-gel Supraglotic Airway from Intersurgical: An introduction. 2016 [cited 2020 April 30th]; Available from: https://www.quadmed.com/product/i-gel-supraglottic-airway.

-

Duckworth, R.L. How to Read And Interpret End-Tidal Capnography Waveforms. 2017 08/01/2017 [cited 2020 April 13th]; Available from: https://www.jems.com/2017/08/01/how-to-read-and-interpret-end-tidal-capnography-waveforms/.

-

Emerging Infectious Disease COVID-19 Transport. 2020 3/2020 [cited 2020 April 30th]; Available from: https://naemsp.org/resources/covid-19-resources/clinical-protocols-and-ppe-guidance/.

Edited by Alison Leung, MD (@alisonkyleung)