Background: Prehospital STEMI identification plays a critical role in ensuring appropriate destination decision and shortening times to reperfusion for patients with acute myocardial infarction. Computer-based ECG interpretation is used in many systems as an adjunct to paramedic interpretation to facilitate prehospital STEMI identification, but like clinician interpretation, remains imperfect. The purpose of this study was to evaluate cases in which the computer algorithm disagreed with the clinical diagnosis of STEMI in order to identify reasons for the discordance and opportunities for improving prehospital STEMI identification.

Methods: The study reviewed 44, 611 consecutive ECGs obtained by Los Angeles County Fire Department using LifePak 15 monitors on patients > 18 years of age with a chief complaint of chest pain, discomfort, or other symptoms in whom paramedics suspect a cardiac etiology, as well as patients at high risk for an acute cardiac event based on medical history, patients with new dysrhythmia, and patients resuscitated from cardiac arrest. In this system, patients are triaged as a STEMI if the LifePak 15 interprets “ACUTE ST ELEVATION MI CRITERIA” and cardiac catheterization lab activation is determined by review of the transmitted ECG by an Emergency Physician at the receiving hospital, sometimes in consultation with Interventional Cardiology.

Only one ECG was reviewed per patient. This preferred ECG was the first ECG of sufficient quality (interpretation and no quality statement). Cases were classified as emergent angiography indicated if the Los Angeles County EMS STEMI database (which tracks all cases of STEMI brought in by EMS), either indicated any of the following outcomes: PCI was performed, PCI was not performed due to need for emergent CABG, intra-aortic balloon placement, difficult catheterization, multivessel coronary artery disease, coronary artery vasospasm or patient death, or the Cardiac catherization lab was canceled due to patient factors such as dye allergy, refusal of treatment, lack of availability, presence of DNR or significant comorbidity. Cases were classified as emergent angiography not indicated if patient underwent catheterization with no lesion or vasospasm, CCL was cancelled or not activated secondary to physician interpretation, or ECG with prehospital diagnosis of not STEMI was not found in the STEMI registry which includes all cases of STEMI diagnosed in the field or in the ED. In cases where the prehospital ECG was interpreted as STEMI, but the patient was not included in the registry, ECGs were reviewed by Cardiology in blinded fashion.

All False Negative and False positive ECGs were classified according to the reason for discordance.

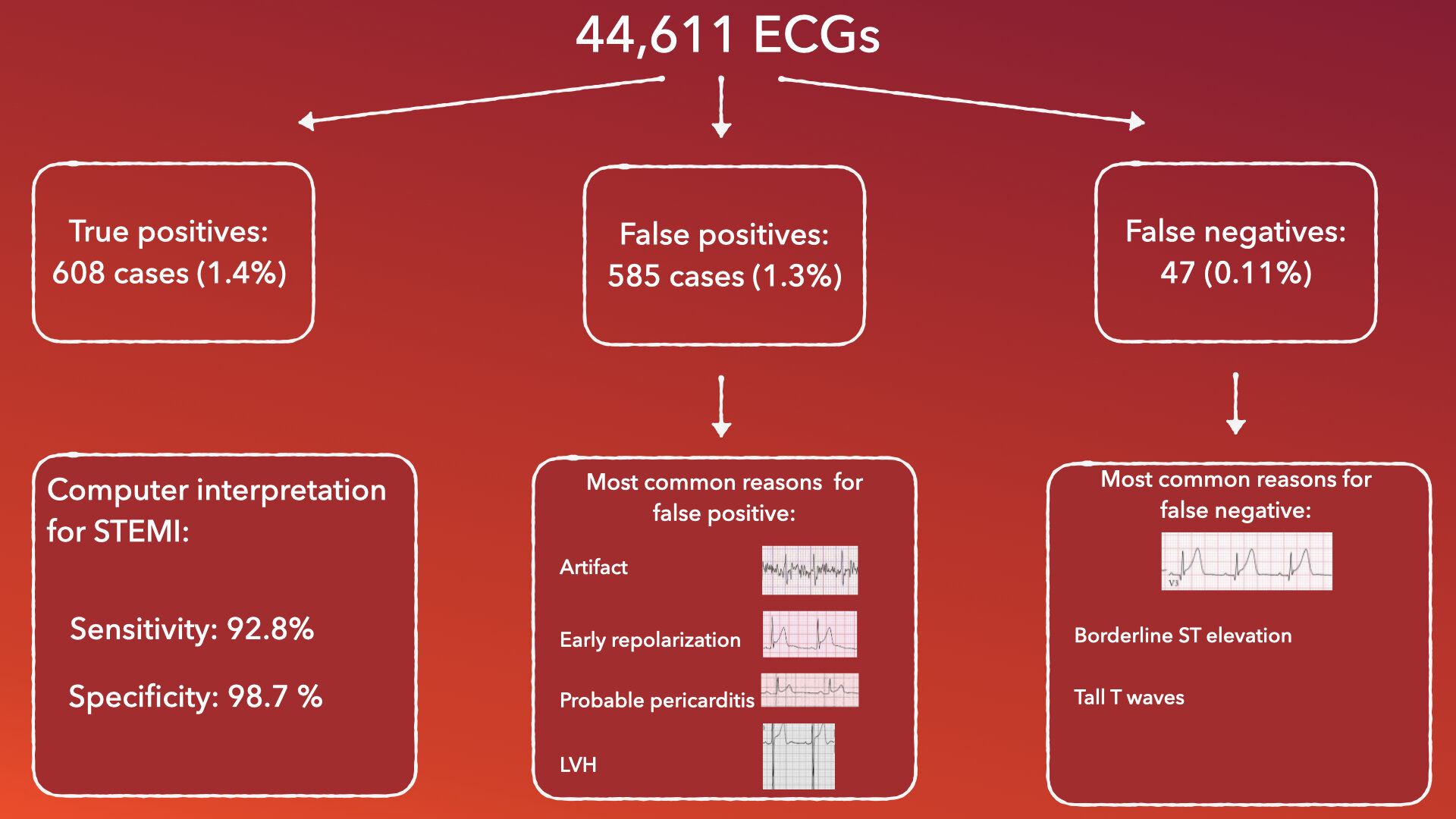

Key Results: 44,611 ECGs were included in the study. There were 482 true positives (1.1%), 711 False positives (1.6%), 43,371 True negatives (97.2%) and 47 (0.11%) false negatives. Of the 126 of the ECGs classified as false positives were subsequently classified as appropriate for emergent coronary angiography when causes of FP STEMI were later assessed and ECGs demonstrated STEMI equivalent or ST elevation in a vascular distribution. With reclassification of these ECGs as false positives to true positives, the sensitivity of computer interpretation for diagnosis of STEMI was 92.8% [95% CI 90.6, 94.7%], Specificity of 98.7% [98.6%, 98.8%], positive predictive value 51.0% [48.1%, 53.8%], and negative predictive value of 99.9% [99.9%, 99.9%]. The high negative predictive value is inflated by the very low prevalence of STEMI in this population.

Leading causes of false positives were ECG artifact (20%), early repolarization (16%), probable pericarditis/myocarditis (13%), indeterminate (12%), left ventricular hypertrophy (8%) and right bundle branch block (5%). Leading causes of false negatives were borderline ST segment elevation (40%), and tall T waves that reduced the ST/T ration below the algorithm threshold (15%).

Conclusions: Primary opportunities for improving prehospital 12 lead interpretation include minimizing ECG artifact, including paramedic and/or physician interpretation into decision making and improving software performance.

What this means for EMS: While automated ECG interpretation has reasonable sensitivity for prehospital STEMI identification, it should not be used in isolation. Paramedic and physician judgement should be used as well. In addition, ECG quality matters and is the most common reason for false positive cath lab activation, representing a significant improvement opportunity.

Article Summary by Maia Dorsett, MD PhD FAEMS, @maiadorsett