Article Summary by James Li, MD

Background:

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a blunt or penetrating trauma to the head that disrupts normal brain function. The CDC estimated approximately 2.5 million emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and deaths in the United States in 2010 for TBI. TBI has an enormous impact on health and healthcare costs in the United States. (1) Primary prevention of TBI consists of preventing the injury from occurring (helmet use, road safety, fall prevention, etc). The goal of medical treatment for patients who have suffered TBI involves minimizing secondary injury which begins hours to days after the primary injury. Secondary injury can involve pathophysiologic processes such as cerebral edema, metabolic derangements, hypoperfusion, excitotoxicity, and more. (2) This study implemented prehospital TBI guidelines based on Brain Trauma Foundation into the Arizona EMS system and looked at patient outcomes. (3)

Methods:

This study took place in Arizona using a controlled, before-after, multisystem, intention-to-treat design. Every EMS agency in Arizona was invited to participate (included >130 agencies and >11,000 EMS providers). The data was collected from the Arizona State Trauma Registry and information from included patients was linked to EMS data from participating agencies (98.7% linkage). The study included adults and children with trauma who were transported to a trauma center by participating EMS agencies, had hospital diagnosis consistent with TBI, and met definition for major TBI (CDC Barrell Matrix Type 1 and/or Abbreviated Injury Scale-Head of at least 3) between January 1st 2007 to June 30th 2015. The implemented guidelines focused aggressive prevention and treatment of hypoxia, hyperventilation, and hypotension. The primary outcome was survival to hospital discharge and secondary outcome was survival to hospital admission.

Results:

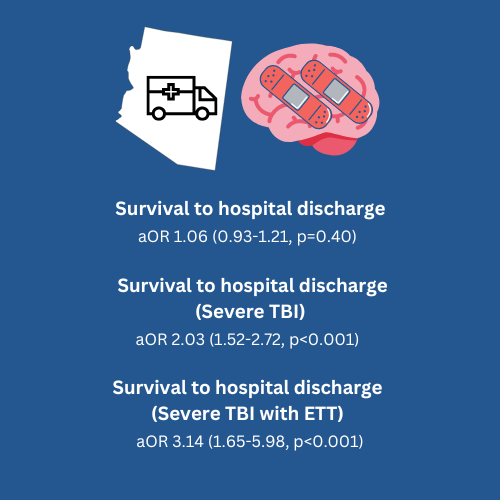

The study enrolled 15,228 patients in the pre-implementation phase and 6624 patients in the post-implementation phase. Implementation was associated with improved treatment to prevent hypoxia, hyperventilation, and hypotension. The overall pre-implementation/post-implementation analysis across all severities (moderate, severe, critical) did not show improved survival to hospital discharge (aOR 1.06, 95% CI 0.93-1.21, P=0.40). Survival to hospital admission did improve (aOR 1.70, 95% CI 1.38-2.09, P<0.001).

Among severity cohorts, for severe TBI patients with a Regional Severity Score – Head 3-4 (not moderate or critical), guideline implementation doubled survival to discharge (aOR 2.03, 95% CI 1.52-2.72, P<0.001). In severe TBI patients who were intubated, guideline implementation tripled survival to discharge (aOR 3.14, 95% CI 1.65-5.98, P<0.001).

What does this mean for EMS?

This study suggests that prehospital guidelines for TBI treatment has the biggest impact on patients with severe TBI. Patients with moderate TBI are likely to survive without implementation of these guidelines. Patients with critical TBI may have such a terrible injury that care targeted towards secondary injury prevention does not change survival.

The targeted treatments in the guidelines are relatively simple and inexpensive. These are treatments that EMS providers do daily, and we know a single episode of hypoxia or hypotension has significant mortality consequences for patients. Secondary brain injury occurs soon after primary injury and early intervention may save neurons. Prevention of the “H-bombs” of hypoxia, hyperventilation, and hypotension has a positive impact on patient outcomes. The increase in survival to hospital admission suggests that the prehospital care provided by EMS is making a difference.

A typical EMS agency participated for three years after implementation of guidelines. The authors noted there was potential for decreased adherence to guidelines over time and assessed changes over time by comparing early and late outcomes. The initial improvement of outcomes faded over time which reflects the need for recurrent education and training to prevent diminishing guideline adherence.

References:

1. Frieden, T. R., Houry, D., & Baldwin, G. (2015). Traumatic brain injury in the United States: epidemiology and rehabilitation. CDC NIH Rep to Congr, 1-74.

2. Kaur, P., & Sharma, S. (2018). Recent advances in pathophysiology of traumatic brain injury. Current neuropharmacology, 16(8), 1224-1238.

3. Badjatia, Neeraj, et al. “Guidelines for prehospital management of traumatic brain injury 2nd edition.” Prehospital emergency care 12.sup1 (2008): S1-S52.