Author: Rachel O’Dell, MD; Washington University Emergency Medicine Residency

Editor: Michael DeFilippo, DO

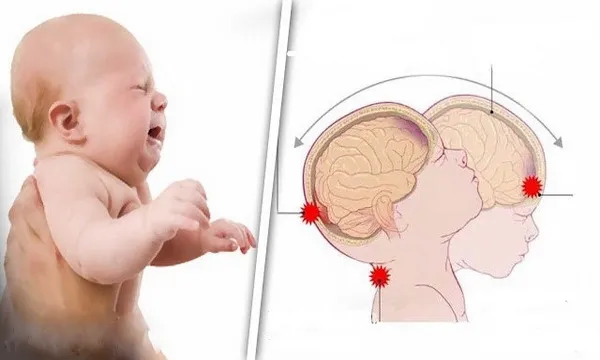

As first-responders, EMS personnel are in a unique position to observe and categorize the setting and behaviors of children presenting with possible non-accidental trauma (NAT). However, children, and especially infants, pose a particular difficulty in identifying trauma due to their subtle presentation. While traditional training focuses on identifying patterns of injury such as stocking burns, bite marks, and belt buckle bruises, these may not always be present during the initial evaluation due to the unique physiology of children, including their relatively small ribcage and incompletely ossified bones. In the setting of EMS, NAT may present in a multitude of seemingly unrelated symptoms, further complicated by the common delay in seeking help after intentional abuse and the vague stories often surrounding the mechanism of injury.

Non-accidental trauma, particularly in infants, often presents as traumatic brain injury, which may not be evident upon initial external examination. These infants often present with respiratory depression, seizure, or even cardiac arrest (1,2). These symptoms are often severe due to delays in caregivers seeking medical assistance, which allow the infant’s condition to deteriorate significantly. While seizures may result from epilepsy or febrile causes, it is crucial to consider NAT in the differential diagnosis. Observing caregivers’ interactions and critically evaluating the provided history are essential steps.

It is critical to prioritize non-accidental trauma in the differential diagnosis for pediatric patients, not just as a possibility to include, but as one to actively exclude. This is particularly true for infants 12 months old and younger, who consistently represent a majority of abuse cases in multiple studies and suffer the highest mortality rates from intentional trauma (1-3). This needs to be an active and concerted effort on behalf of both trainers and first responders, since it has been shown by Qualls et. al. that EMS providers are excellent at recognizing and documenting external signs of abuse, but they rarely document nonspecific signs such as seizures and vomiting (3)..

EMS providers are uniquely positioned to not only document potential signs of abuse but also take immediate, impactful action to stabilize these vulnerable patients and prevent further harm. Recognizing both the subtle and overt signs of traumatic brain injury allows EMS personnel to make meaningful, lasting impacts on the populations most vulnerable to NAT-related brain injuries, particularly infants, who face the highest risk of death or lifelong complications from their injuries. It has been well established that in the first presentation and initial stabilization of traumatic brain injuries it is imperative to maintain adequate oxygenation, normothermia, normoglycemia, and prompt intervention on seizures (4). The EPIC4Kids trial demonstrated that pre-oxygenating children with traumatic brain injuries is not only safe but also significantly improves outcomes for the most severe cases (5).

EMS personnel are not only poised in the perfect place for initially raising concerns for NAT and preventing reinjury. They are in the unique position to provide lasting interventions on behalf of the victims in both their survival and their degree of permanent disability. This is an arena where first responders are not only able to prevent reinjury and emotional distress inflicted by caregivers, but to also improve the future ahead of their patients.

- Eysenbach L, Leventhal JM, Gaither JR, Bechtel K. Circumstances of injury in children with abusive versus non-abusive injuries. Child Abuse Negl. 2022;128:105604. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105604

- Loos MHJ, van Rijn RR, Krug E, et al. The prevalence of non-accidental trauma among children with polytrauma: A nationwide level-I trauma centre study. J Forensic Leg Med. 2022;90:102386. doi:10.1016/j.jflm.2022.102386

- Qualls C, Hewes HA, Mann NC, Dai M, Adelgais K. Documentation of Child Maltreatment by Emergency Medical Services in a National Database. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2021;25(5):675-681. doi:10.1080/10903127.2020.1817213

- Flowers D, Berkoff M. Child maltreatment. In: Cone DC, Brice JH, Delbridge TR, Myers JB, eds. Emergency Medical Services: Clinical Practice and Systems Oversight. Wiley; 2021:498-501. doi:10.1002/9781119756279.ch62

- Gaither JB, Spaite DW, Bobrow BJ, et al. Effect of Implementing the Out-of-Hospital Traumatic Brain Injury Treatment Guidelines: The Excellence in Prehospital Injury Care for Children Study (EPIC4Kids). Ann Emerg Med. 2021;77(2):139-153. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2020.09.435