Authors: Rebecca Dupree, DO and Emerson Franke, MD FAEMS FAAEM

Case

The dreaded scenario: you’re performing high quality CPR in the field, you’ve successfully intubated the patient, and suddenly you hear, “I found their DNR form!” just as you’ve gotten ROSC. You manage to get in contact with family and determine the patient is enrolled in hospice. The family does not want the patient transported to the hospital. So what do you do?

Literature Review

Few case studies have touched on the subject of terminal extubation performed by EMS providers during the initial patient contact. Most of these involve transport home, with a hand off to the hospice team after carefully detailing the extubation and transport processes. More commonly, patients are transported to the Emergency Department (ED), where extensive conversations between ED providers and family occur. These may result in an ED extubation or admission to the hospital for comfort care and terminal extubation. However, for terminally ill hospice patients who have wishes to remain at home, is this truly in the best interest of the patient? This puts an added emotional toll on families, especially if the patient had forms stating their wishes that were unfortunately accessed too late. A recent JAMA article showed that dying in the hospital led to an overall prolonged state of grief and distress for families as well as a suboptimal care for patients and families. EMS providers are equipped with the skill to intubate patients, and could be taught to extubate and provide palliative care.

Terminal extubation tends to carry a negative connotation, especially when speaking with families. We suggest a change from “terminal” to “palliative” extubation, as that is truly the end goal. Hospice mainly aims to prioritize the comfort of patients, as well as make resources available that otherwise would be difficult to come by. Families hear “terminal” and believe they will be causing their loved ones death, or that the patient will be suffering during the process. The priority of EMS leaders is to establish a protocol that ensures the needs of both the family and the patient are met. EMS clinicians should have access to morphine or other pain control agents, lorazepam or other anxiolysis medications, and glycopyrrolate or atropine to help control secretions.

Prehospital providers must focus on the needs of the patient but also be aware of the needs of family members. They should explain the process and what to expect, especially as many extubated patients will not die immediately. Because of this possible prolonged process, the hospice team should be contacted early and a plan should be made by the hospice team on what medications to administer and how often if an existing protocol does not exist. They should also have follow-up plans in place should the process be more prolonged, including discussing with their supervisors and dispatch. As the EMS team may not be able to remain with the patient for an extended time, another provider should be notified to continue to administer medications

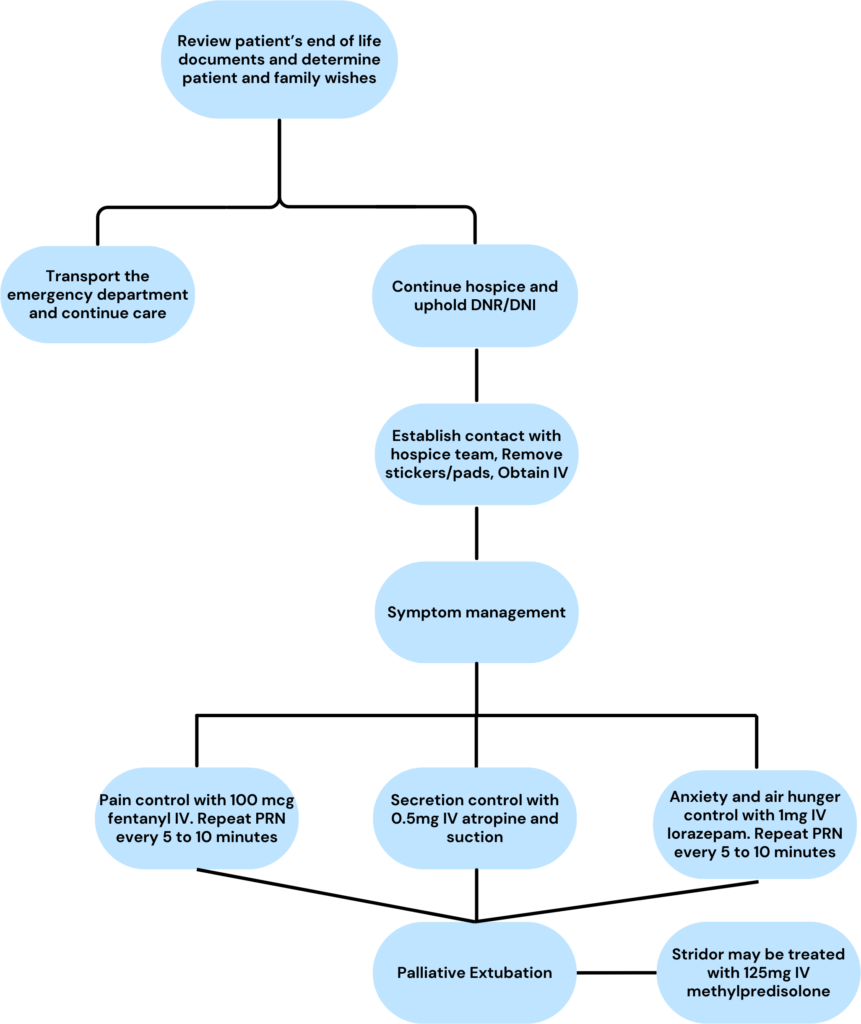

An example flowchart of the process by the authors is provided below.

One of the biggest hurdles of this is reframing the mindset for the EMS team, as ceasing care is in direct antithesis to their training. Even in the emergency department, we are extensively taught for years how to save lives but have very few lessons on allowing them to end, accounting for the far too infrequent end of life care discussions that tend to occur. This creates emotional turmoil for clinicians, especially in the prehospital setting where limited resources are available.

The role of EMS in palliative care has recently gained traction, especially with the ever-aging population. According to Medicare reports from 2020, approximately 1.72 million people in the United States were taken care of through hospice services. This constitutes a 6.8% increase from the prior year. Though some of this is related to the pandemic’s effect on deaths in the United States, the yearly rate of rise of patients entering hospice care has steadily increased yearly since 2015. The steady rise increases the likelihood of prehospital providers interacting with this special population, and highlights the need for policies related to hospice care.

References

- Elmer J, Mikati N, Arnold RM, Wallace DJ, Callaway CW. Death and End-of-Life Care in Emergency Departments in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(11):e2240399. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.40399

- Michas, F. (2023, June 5). Hospice patients number served U.S. 2009-2020. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/339851/number-of-hospice-patients-in-the-us-per-year