Melody Glenn, MD

One by one, people start to arrive at Greasebox, a local diner in Oakland, CA, for our inaugural multidisciplinary book club session. Only a few of the faces are familiar to me — my colleagues in emergency medicine and EMS, but the rest introduce themselves as students and practitioners working in sociology and public health. I am not sure if they were attracted by our objective — to discuss issues loosely related to EMS from a multifaceted approach — or that the author, Seth Holmes MD PhD, of our first book, Fresh Fruit, Broken Bodies, was here to provide his own personal insights to our bookclub.

In his book, Dr. Holmes delves into a time between his medical school and residency, when he lived and worked with a group of migrant farmworkers, beginning with their dangerous journey across the US-Mexico border. Although he is detained in an Arizona Jail, he continues forward. He follows his adoptive family to various farms along the West Coast, living in substandard living conditions and developing chronic pains from hours in the fields. Why would a young physician want to subject himself to living a life in destitution, danger, and hard-labor? For his anthropology fieldwork, Dr. Holmes’ was committed to observing and recording the health and socioeconomic issues related to a population that is largely undocumented and thus uninsured. As a result, almost all migrant workers find it difficult to access many American medical services outside of primary care clinics, emergency departments, and Emergency Medical Services (EMS).

Their jobs and living conditions expose them to a high burden of illness and trauma. Agricultural workers have a fatality rate five times that of all workers, and increased rates of nonfatal injuries, musculoskeletal pain, heart disease, cancer, stillbirth, and congenital birth defects. Their children have high rates of malnutrition, vision problems, dental problems, anemia, and lead poisoning. Specifically, Holmes uses three case studies — Albelino’s knee, Crescencio’s headaches, and Bernado’s stomach pains — to clearly demonstrate how our medical system fails this population because we don’t recognize the environment they live in or the root causes of their pathology. The medical system, and their physicians, failed them.

However, as Holmes was not yet a practicing physician at the time of writing his book, his analysis sometimes feels too disconnected from the realities of clinical constraints and modern healthcare. Even if we identify the structural factors causing our patients’ illnesses, we, EMS providers and EM physicians, do not have the tools to solve them. In my 15-minute emergency department visit, I can’t arrange for fair working conditions or safe housing. It is even more constrained in the prehospital world. As emergency providers, what can we really do?

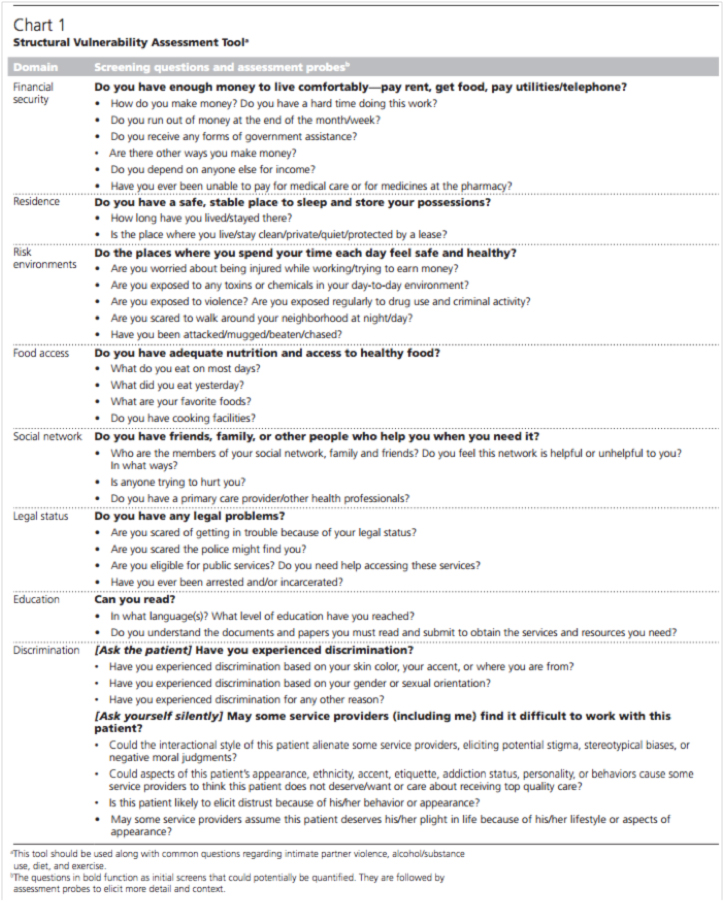

In response, Dr. Holmes refers us to a paper that he wrote with Phillippe Bourgois titled, “Structural Vulnerability: Operationalizing the Concept to Address Health Disparities in Clinical Care,” which included a vulnerability assessment tool that can be utilized in our medical assessments. He also recommended including our patients’ barriers to care in our patient’s H&P, even if we cannot directly fix them, so that they become a formalized part of the patient narrative for other providers to see and incorporate. Lastly, if we see certain issues come up over and over again in multiple patients’ assessments, we can work with local advocacy and policy groups to affect large-scale change.

The next week, we tried to put these words into action; an EM resident from the book club used the vulnerability assessment tool during a clinical shift. He noticed that although it took only 35 seconds to read out the questions, the answers took significantly more time. He also did not feel qualified to address their needs. Instead of having the physician ask the questions on the assessment tool, perhaps there could be a health coach on-staff in order to screen high-risk patients and integrate local social service organizations into the ED milieu.

And that’s when it hit me…maybe there is a role for EMS in this whole complicated issue. We know that paramedics actually meet patients where they are — whether that is the street or their home — and have the unique ability to see first hand some of the structural barriers to effective medical treatment that patients might face, such as homelessness, polysubstance abuse, lack of insurance, and lack of a social support network. As a result, I’m working with local partners to incorporate aspects of the structural vulnerability assessment tool into the ePCR so that paramedics have a way to catch patients that they deem high risk of failing medical treatment because of these barriers. For example, when you make your 5th call on that patient living in a dirty Single Room Occupancy (SRO), who is lying in a urine-soaked mattress with a half-drank bottle of vodka at his bedside — are you surprised that he is again suffering from a CHF exacerbation? If a patient scores high on the prehospital screening tool, they can be referred to a community paramedicine initiative.

Overall, Dr. Holmes’ book Fresh Fruit, Broken Bodies is a solid narrative that takes you through a personal journey of the hardships experienced by our migrant workers, illuminating many of the structural issues that get in the way of their health. As the book’s success weighs heavy on its thoughtful content and sociologic theory, don’t expect it read like a page-turning novel. I believe that chapters 1, 4, and 5 have the most relevance to healthcare providers, and recommend you read them in order to deepen your understanding of the barriers that this population faces. Even if you do not work directly with undocumented people or farmworkers, you will come away with a new perspective that can improve your patient care.

Next book: Five Days at Memorial by Sheri Fink

Five Days at Memorial is the Pulitzer Prize winning work by Sheri Fink, New York Times reporter and physician, about a hospital that faced difficult life-and-death decisions during Hurricane Katrina.

When: January 5, 2016, 6-8 pm Pacific

How to participate: Share thoughts and questions below, or tweet them live to @MGlennEM during the event!

If you want to listen to a great podcast to get you excited, check out the radiolab episode!