by Melody Glenn, MD

The voice on the other end of the phone sounds frantic and rushed, “He can’t breathe!” The palpable panic wakes the emergency dispatcher out of his post-lunch daze. He sits up a little straighter and shifts his gaze to the periphery, preparing to listen more closely. “Okay, tell me exactly what happened.”

“My son is allergic to peanuts, and I think he accidentally ate some. He is wheezing and his voice sounds muffled. Are you sending someone?!”

“Yes, I’m sending the paramedics to help you now. Stay on the line and I’ll tell you exactly what to do next.” As he flips to the epinephrine auto injector card, he asks, “Does he have any specific injections or other medications to treat this type of reaction?”

“He used to have an epi-pen, but we used it a few months ago. When I went to refill his prescription, it was $600! Please, hurry!”

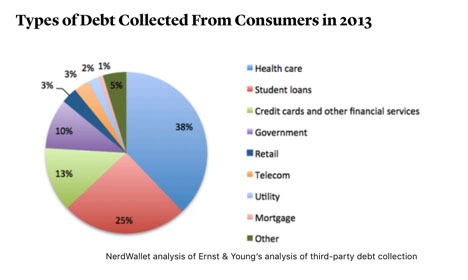

We have all heard about the exorbitant price increases in epinephrine, narcan, and albuterol, and may have seen firsthand the impacts on patient care. But what is the story behind these increases? In An American Sickness, Elisabeth Rosenthal attempts to break down some of the perverse incentives that lead to rising healthcare costs, costs that quickly add up. Healthcare bills now comprise the greatest percentage of consumer debt, and medical debt is the number one reason why Americans file for bankruptcy.

Image source: https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2014/10/why-americans-are-drowning-in-medical-debt/381163/

Rosenthal trained in internal medicine, worked for a few years in an ER, and then switched careers to become a journalist/editor. Although sometimes her tone is overly strong, making the writing feel like more of an OpEd than nonfiction, and some of her examples are made to appear more black-and-white than clinical medicine actually is, the overall message rings true. Health care is a highly profitable industry with a lot of players scrambling to augment their slice of the pie. As such, healthcare isn’t going to regulate itself.

The first half of the book delves into the problem. Each chapter focuses on a different segment of the healthcare sector, including pharmaceuticals, insurance companies, hospitals, physicians, and medical devices, showing how each has been guilty of prioritizing their own financial gain over patient value. In our bookclub discussion, we looked at examples that seemed to hold the most relevance to EMS, the first being the shortage of generic medications. Perhaps the most notorious example is that of Droperidol, and the almost conspiratorial series of events surrounding its disappearance (p. 119-122).

Around 2005, GlaxoSmithKline started to promote the use of Zofran for general nausea, as initially, it had just been marketed as a treatment for chemo-induced nausea. Around that same time, the FDA issued a black box warning linking Droperidol to life-threatening arrhythmias, and a major pharmaceutical company purchased and subsequently closed the plant that was producing the generic compazine. Physicians were stuck using Zofran, which cost several times that of its generic competitors. Some doctors filed a Freedom of Information Act to obtain the documents that lead to the FDA’s warning. In the documents, they found that the abnormal heart rhythms were only induced by administering Droperidol in very high quantities — 50-100 times greater than the standard amount — and that the same arrhythmias could be provoked by high doses of other anti-nausea drugs (including Zofran). Since then, Glaxo has reached a $3 billion settlement with the U.S. Department of Justice for a variety of misdeeds, but Zofran continues to earn a profit.

Rosenthal also addresses the potential for conflicts of interest in the creation of clinical guidelines (p.200-204). When specialists write their own guidelines, they have financial incentives to promote their own procedures. For example, urologists recommended that all men be screened with a PSA level, radiologist’s advised yearly mammograms, and orthopedists encouraged arthroscopy to help with knee pain. These recommendations have since been revised based on new evidence questioning their benefit. Although the majority of EMS and emergency medicine position statements and guidelines address common conditions and do not encourage expensive diagnostics or treatments, we still get paid for doing more to our patients. It remains true that very often we work harder to do less, both in terms of time for shared decision making, patient discussion and documentation, and get paid less to so. In EMS, the system aligns financial incentives with transport, which is our default mode, whether or not this is best for the patient.

In Chapter 9, Rosenthal suggests that the trend towards hospital consolidation often leads to increased costs and decreased quality. Although initially billed as a way to obtain lower rates through economies of sale, this isn’t necessarily what occurs (p.207). When one network owns all of the local hospitals and clinics in an area, and employs the majority of physicians, there is no longer any competition. This effectively gives the conglomerate the leverage needed to demand high rates from corporations, insurers, and HMO’s (p. 207). They can also use their proprietary electronic medical record system as a tool to keep competitors out, which is antithesis to the original intent of moving towards EMR systems (211). Although Rosenthal doesn’t mention EMS in this context, I wonder if the same cautions apply.

Rosenthal only devotes a few pages to EMS (p.157-160), and they don’t seem particularly well-informed. She seems longful for the days when ambulance services were free (p.158). She doesn’t seem to understand that quality has improved and that EMS is now predominantly staff by medical professionals and considered a medical subspecialty. Instead, she attributes the rise in cost to the use of professional billing companies (p.159). Also, she doesn’t address the cost of preparedness. It takes time, preparation, training, and money to be ready to handle any emergency at any time.

Part II of the book provides various strategies that individuals, institutions, and policymakers can implement in order to fix the rising costs of healthcare. She suggests that individuals ask their clinicians how much various diagnostic and treatment options cost. I imagine many would not know, as we are purposefully not taught this information in medical school or residency because of the notion that cost should not drive our decision whether or not a treatment is clinically necessary. Also, there is little price transparency in our medical system, so it is hard for us to even get this information from our own hospital finance departments. Therefore, she also suggests that patients do their own research. In Appendices A and B, she shares various websites where patients can find the “fair price” for a large number of procedures and medications and see how your hospital compares. Of course, this is less useful in emergency situations.

From the policy perspective, she gives several concrete suggestions, including that:

· Limits be placed on economic damages in malpractice lawsuits

· Medical practices offer warranties and guarantees (reducing the need for malpractice suits)

· Drug companies obtain approval before ceasing a drug’s production

· The FDA reform their drug patent process to promote low-cost generics

· The US government work harder to negotiate and set national drug prices

· A public option of Medicare be available

· There is more regulation over health insurance companies

· The Federal Trade Commission become more involved in using antitrust law to break up large conglomerates

Although these solutions, much like the rest of the book, are not written specifically for emergency medicine or EMS, the overall ideas are still relevant. The book’s strong tone is likely designed to serve as a call to action. We should take this an an opportunity to ask ourselves — how can EMS be involved in reforming our country’s healthcare system?

Special thanks to John Brown, MD, MPA, the medical director of the San Francisco EMS Agency and program director of the UCSF-ZSFG Fellowship in EMS and Disaster Medicine, and Thomas Sugarman, MD, FACEP, FAAEM, Secretary-Treasurer of the Alameda Contra Costa Medical Association, Co-Chair of the East Bay Safe Prescribing Coalition and a Past-President of the California chapter of the American College of Emergency Physicians, for adding their expertise to the bookclub discussion.