by Aaron Farney MD

Clinical Scenario

You are called for a 25-year-old male, possible overdose, unknown if breathing. On arrival, the patient is unresponsive on his bathroom floor. Family reports they found him on the floor not breathing just prior to calling 911. They had last seen him well 15 minutes prior. He has a known history of heroin use, and you notice an empty syringe next to him. On exam, he is unresponsive, cyanotic, with agonal respirations and has a pulse of 40.

You immediately commence resuscitative measures. The airway is positioned, a nasopharyngeal airway is inserted, and positive pressure ventilations are initiated via a bag-valve mask connected to high-flow oxygen, with resultant resolution of cyanosis. Four milligrams intranasal naloxone is administered. About three minutes later, the patient wakes and you start to notice copious pink, frothy secretions. You suction, but it continues, and even seems to increase. The patient is now alert, complaining of shortness of breath and hypoxic to 78% despite a non-rebreather mask flowing at 15 liters/minute. Your partner asks you “did he aspirate…?”

What is happening, and what is the correct management?

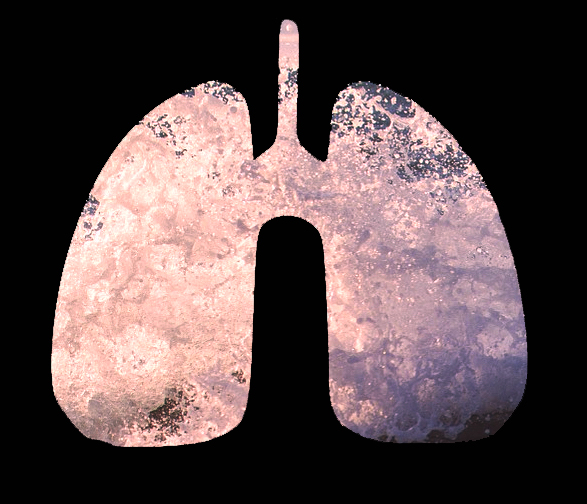

The phenomenon of opioid-related noncardiogenic pulmonary edema (NCPE) is not widely known in the prehospital realm. As we are in the midst of an opioid crisis, the odds that the average field provider will encounter opioid-related NCPE is increasing. The ability to recognize this phenomenon and knowing what to do will make all the difference to your patient.

Background & Prevalence

The physician William Osler first described narcotic-related pulmonary edema during an autopsy in 1880 [1,2]. Its presentation and clinical course was not appreciated until the 1950s-60s. The prevalence of opioid-related NCPE is about 2-10% of heroin overdoses [1,2]. It is most commonly seen in heroin overdose but has been reported with other opioids.

Presentation & Clinical Course

Opioid-related NCPE typically presents as dyspnea accompanied by development of pink, frothy pulmonary secretions associated with ongoing hypoxia despite reversal of respiratory depression with an opioid antagonist (i.e. naloxone). It often presents immediately after reversal but can be slightly delayed, up to four hours [1]. Most cases will resolve within 24-36 hours, but up to one-third of cases will require aggressive respiratory support [1,2]. If left untreated, it can progress to complete hypoxic respiratory failure, hypoxic end-organ injury, and cardiac arrest.

Pathophysiology

The mechanism of opioid-related NCPE is poorly understood, in part because there are a variety of drugs involved, including the opioid antagonist naloxone. There are several published theories. Perhaps the most popular theory is increased pulmonary capillary permeability related to hypoxia and/or histamine release [1,2]. Heroin in particular is prone to causing excessive histamine release, causing leaky pulmonary vasculature. Morphine is another drug known to do this.

Other theories blame naloxone. A patient who is opioid dependent, overdoses, and who is rapidly reversed with a high dose of naloxone subsequently experiences a catecholamine surge, particularly in those with concomitant cocaine use. [2] A second theory blaming naloxone is that following a prolonged period of near or complete apnea, reversal that results in inspiratory effort prior to complete opening of the glottis can result in excessive negative pressure within the lung, drawing in fluid from the pulmonary vasculature. Administering positive pressure ventilation prior to naloxone therapy may mitigate this. It is likely that opioid-related NCPE is multifactorial, with both the opioid agent and naloxone contributing. Regardless of the underlying etiology, treatment remains the same.

Management

The treatment of opioid-related NCPE is supportive and focused on correcting hypoxemia. Initial measures include application of supplemental oxygen, preferably via a non-rebreather mask. Patients with hypoxia refractory to high flow O2 warrant assisted ventilations. Paramedics should have a low threshold for initiating CPAP therapy in the patient experiencing opioid-related pulmonary edema. Hypoxemia or distress refractory to CPAP therapy may warrant endotracheal intubation and invasive ventilation to correct hypoxemia. There has been no identified role for nitroglycerin or other medications in treating opioid-related NCPE.

Back to the case:

The medic recognizes that this patient is experiencing opioid-related NCPE. Only 8 minutes from the nearest emergency department, RSI is deferred in favor of immediate transport. CPAP is placed onto the patient at a pressure of 5 cm H20. The patient tolerates CPAP well, and oxygenation is improved to 90% on arrival at the emergency department, where care is transferred. The patient continues to improve on CPAP and is admitted for further monitoring.

Take-home points:

-

EMS should administer only the amount of naloxone required to reverse respiratory depression, not mental status. Higher doses may increase risk of NCPE.

-

Opioid-related NCPE occurs in about 2-10% of opioid overdoses

-

Patients may complain of shortness of breath and will develop pink, frothy pulmonary secretions and hypoxia despite opioid reversal

-

Treatment is focused on correcting hypoxemia with supplemental oxygen and CPAP

-

Cases refractory to CPAP may require invasive ventilation

-

All patients with opioid-related NCPE warrant transport.

References

1. Sporer KA & Dorn E. Heroin-Related Noncardiogenic Pulmonary Edema: A Case Series. Chest 2001; 5:1628-1632.

2. Sterrett et al. Patterns of Presentation in Heroin Overdose Resulting in Pulmonary Edema. American Journal of Emergency Medicine 2003; 21:32-34.

3. Grosheider T & Sheperd SM. Chapter 296: Injection Drug Users. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine 8th ed. 2016.