By Nicholas Maxwell, MD

Case:

You are bringing an elderly male with a DNR back to a living facility from a hospital. Approximately 10 miles away from the hospital, the patient suddenly decompensates. His pulse ox drops from 94% to 87% and his heart rate increased from about 110 beats per minute to approximately 180. His mental status is described as nodding off. The EMS crew reports that the hospital was unclear if he was on hospice or if he simply had a DNR. They were also reportedly unclear about what level of care the facility he was being returned to had.

Literature Review:

Education in EMS often focuses on how to treat acutely ill and injured patients with the goal of saving lives and preventing serious, long-lasting negative outcomes. Since their training is so focused on acute, life-threatening illness, they are often called to help those who are acutely ill/injured and/or dying. However, at most EMS education programs, very little, if any, time is spent teaching how to care for patients who are not interested in resuscitation and life-saving interventions, such as hospice patients.

Hospice patients in particular flip the oft assumed goal of resuscitation and life-saving interventions that EMS is so adeptly trained to execute. In these patients, resuscitation is essentially contraindicated, and the primary goal is often to prevent/relieve suffering, even if it means death comes quicker than if you were to provide aggressive interventions. This can often be uncomfortable for EMS crews as it seems antithetical to what they are trained to do, especially when they see something that they have been trained to treat. After all, by nature of being on hospice, these patients are dying from something, and it can be hard to fight that interventionist approach in a profession that is seen by many as an illness-centered field. However, in actuality, EMS isn’t an illness-centered field. It is a patient-centered field. This can be most apparent at the extreme end of the spectrum where hospice patients reside.

While research suggests that EMS providers find treating these patients to be meaningful and important, it can often be extremely uncomfortable for them, especially considering medico-legal and ethical considerations. These can include feeling compelled to attempt resuscitation despite the team feeling it is futile or not consistent with the patient’s wishes, families demanding CPR despite the presence of a DNR, incompletely filled out DNR forms, and more.

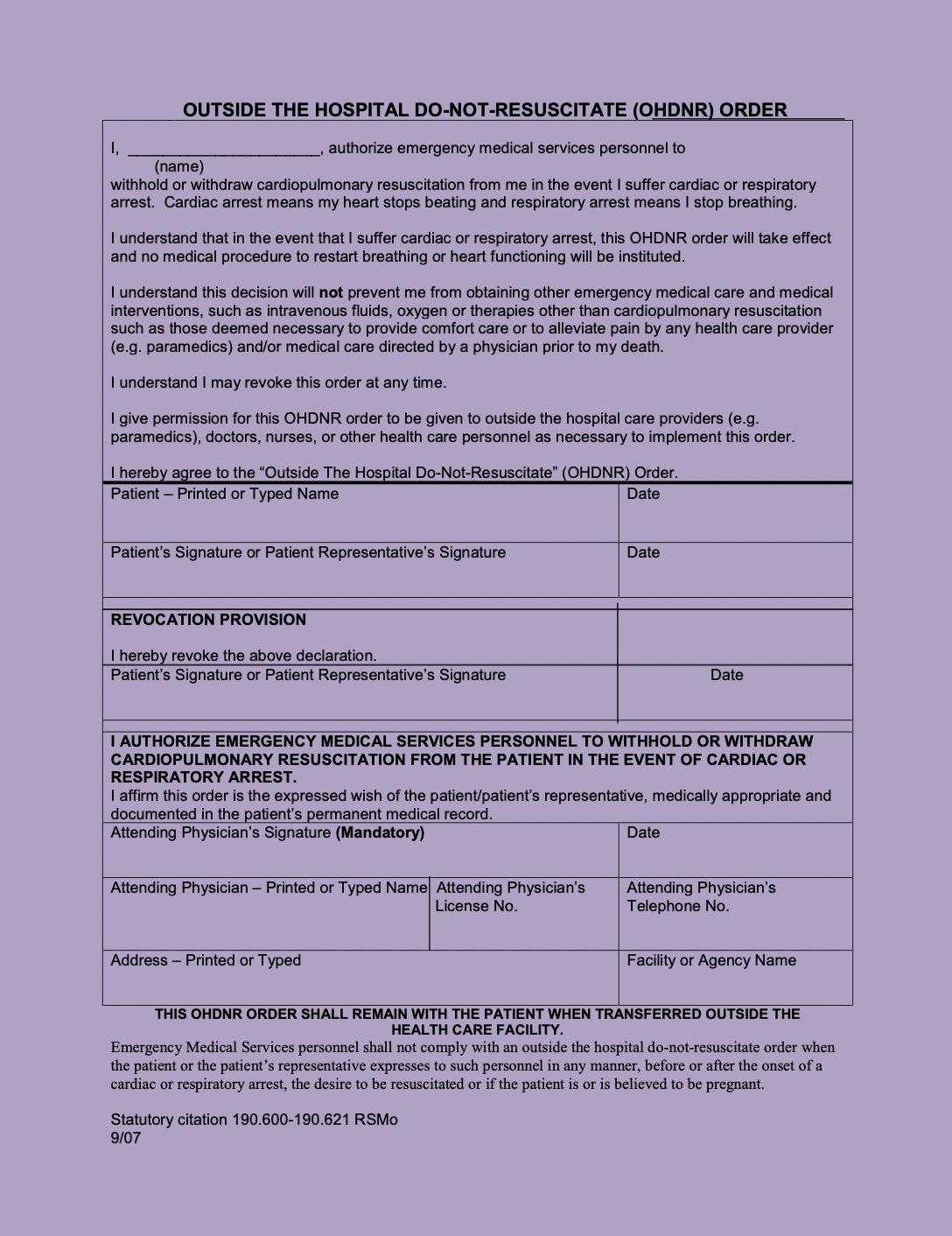

Missouri Out of Hospital DNR Form is shown here. There are also POLST (Physician Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment) forms that describe patient’s treatment preferences in additional detail. Other names for POLST include: MOLST, MOST, TPOPP, and more. EMS professionals should be familiar with their state’s forms.

It is easy to assume that this is a rare occurrence. However, that is not the case. One study reported that 66% of respondents had more than 10 encounters with hospice patients. In fact, only 3.8% of respondents had not encountered hospice patients in their professional experience. The calls can be for a range of reasons such as falls, insufficient symptom management, and family members/nursing facility staff not knowing patient’s status. While it can be easy to assume that since the patient is on hospice, there is no role for EMS intervention, that is not the case. Sometimes they may benefit from transport to an emergency department if it is consistent with their care plan/wishes. One common indication for this might be failure to have a tolerable level of symptom management (for example, pain after a fall). Instead of the oft presumed goal of saving life and limb, these patients need to have special attention paid to determining their wishes. This can require communication skills that are nuanced, not intuitive, and not nearly as intensely trained in comparison to other skills like EKG interpretation and intubation.

Unfortunately, EMS providers often have less than the desired amount of training for these kinds of encounters. One study found that 76% of respondents said they never received formal training on hospice care. 10% even felt that DNR/DNI means no treatment can be provided to the patient. In the setting of this sub-optimal training, it can be hard to know what to do in these stressful and difficult to navigate situations. One study found that 60.8% of respondents reported they had been pressured by families to provide more aggressive care than the patient desired, 28.8% had performed CPR on a hospice patient, and 17.9% had intubated a hospice patient. However, it is worth noting that research suggests that EMS providers find caring for this patient group to be important and meaningful and that they would appreciate additional training on how to serve this group of patients. This additional training may relieve some of the discomfort associated with treating this patient population, improve the care provided, increase patient satisfaction, and in many cases avoid unnecessary transfers to the hospital

There are even some interesting uses of EMS to serve palliative care and hospice patients that have been explored. One particularly interesting example of this is use of EMS for a terminal extubation. The patient was dying while intubated in the ICU but was awake enough to engage in discussions with providers through writing about her wishes. She was adamant that she wanted to be at home even though she was dying and would likely die much faster if she went home rather than staying at the hospital. She was interested in a terminal extubation but they weren’t sure she would survive long enough after extubation at the hospital to make it home. After days of meeting with palliative care, psychiatry, and even the EMS physician, they had her transported via EMS to her home where the EMS physician performed the terminal extubation and care was handed off to the home hospice team.

In sum, while encountering hospice patients is not uncommon in EMS, it is commonly uncomfortable for providers who want to do right by these patients, there is desire for and opportunity for further education in handling patients involved in hospice and end of life care, and this additional training would go a long way in helping EMS be the elite patient-oriented providers that they aim to be.

References:

1. Juhrmann ML, Anderson NE, Boughey M, McConnell DS, Bailey P, Parker LE, Noble A, Hultink AH, Butow PN, Clayton JM. Palliative paramedicine: Comparing clinical practice through guideline quality appraisal and qualitative content analysis. Palliat Med. 2022 Sep;36(8):1228-1241. doi: 10.1177/02692163221110419. Epub 2022 Aug 8. PMID: 35941755.

2. Surakka LK, Hökkä M, Törrönen K, Mäntyselkä P, Lehto JT. Paramedics\’ experiences and educational needs when participating end-of-life care at home: A mixed method study. Palliat Med. 2022 Sep;36(8):1217-1227. doi: 10.1177/02692163221105593. Epub 2022 Aug 3. PMID: 35922966.

3. Bruun H, Milling L, Mikkelsen S, Huniche L. Ethical challenges experienced by prehospital emergency personnel: a practice-based model of analysis. BMC Med Ethics. 2022 Aug 12;23(1):80. doi: 10.1186/s12910-022-00821-9. Erratum in: BMC Med Ethics. 2022 Nov 26;23(1):120. PMID: 35962434; PMCID: PMC9373324.

4. Wenger A, Potilechio M, Redinger K, Billian J, Aguilar J, Mastenbrook J. Care for a Dying Patient: EMS Perspectives on Caring for Hospice Patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2022 Aug;64(2):e71-e76. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2022.04.175. Epub 2022 Apr 28. PMID: 35490992.

5. Breyre A, Taigman M, Salvucci A, Sporer K. Effect of a Mobile Integrated Hospice Healthcare Program on Emergency Medical Services Transport to the Emergency Department. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2022 May-Jun;26(3):364-369. doi: 10.1080/10903127.2021.1900474. Epub 2021 Mar 30. PMID: 33689535.

6. Juhrmann ML, Vandersman P, Butow PN, Clayton JM. Paramedics delivering palliative and end-of-life care in community-based settings: A systematic integrative review with thematic synthesis. Palliat Med. 2022 Mar;36(3):405-421. doi: 10.1177/02692163211059342. Epub 2021 Dec 1. PMID: 34852696; PMCID: PMC8972966.

7. Waldrop DP, Waldrop MR, McGinley JM, Crowley CR, Clemency B. Prehospital Providers\’ Perspectives about Online Medical Direction in Emergency End-of-Life Decision-Making. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2022 Mar-Apr;26(2):223-232. doi: 10.1080/10903127.2020.1863532. Epub 2021 Feb 2. PMID: 33320725.

8. Breyre AM, Bains G, Moore J, Siegel L, Sporer KA. Hospice and Comfort Care Patient Utilization of Emergency Medical Services. J Palliat Med. 2022 Feb;25(2):259-264. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2021.0143. Epub 2021 Aug 31. PMID: 34468199.

9. Surakka LK, Peake MM, Kiljunen MM, Mäntyselkä P, Lehto JT. Preplanned participation of paramedics in end-of-life care at home: A retrospective cohort study. Palliat Med. 2021 Mar;35(3):584-591. doi: 10.1177/0269216320981713. Epub 2020 Dec 18. PMID: 33339483.

10. Waldrop DP, Waldrop MR, McGinley JM, Crowley CR, Clemency B. Managing Death in the Field: Prehospital End-of-Life Care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020 Oct;60(4):709-716.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.05.004. Epub 2020 May 11. PMID: 32437943.

11. Clemency BM, Grimm KT, Lauer SL, Lynch JC, Pastwik BL, Lindstrom HA, Dailey MW, Waldrop DP. Transport Home and Terminal Extubation by Emergency Medical Services: An Example of Innovation in End-of-Life Care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019 Aug;58(2):355-359. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.03.007. Epub 2019 Mar 21. PMID: 30904415.

Editing by EMS MEd Editor James Li MD